Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams

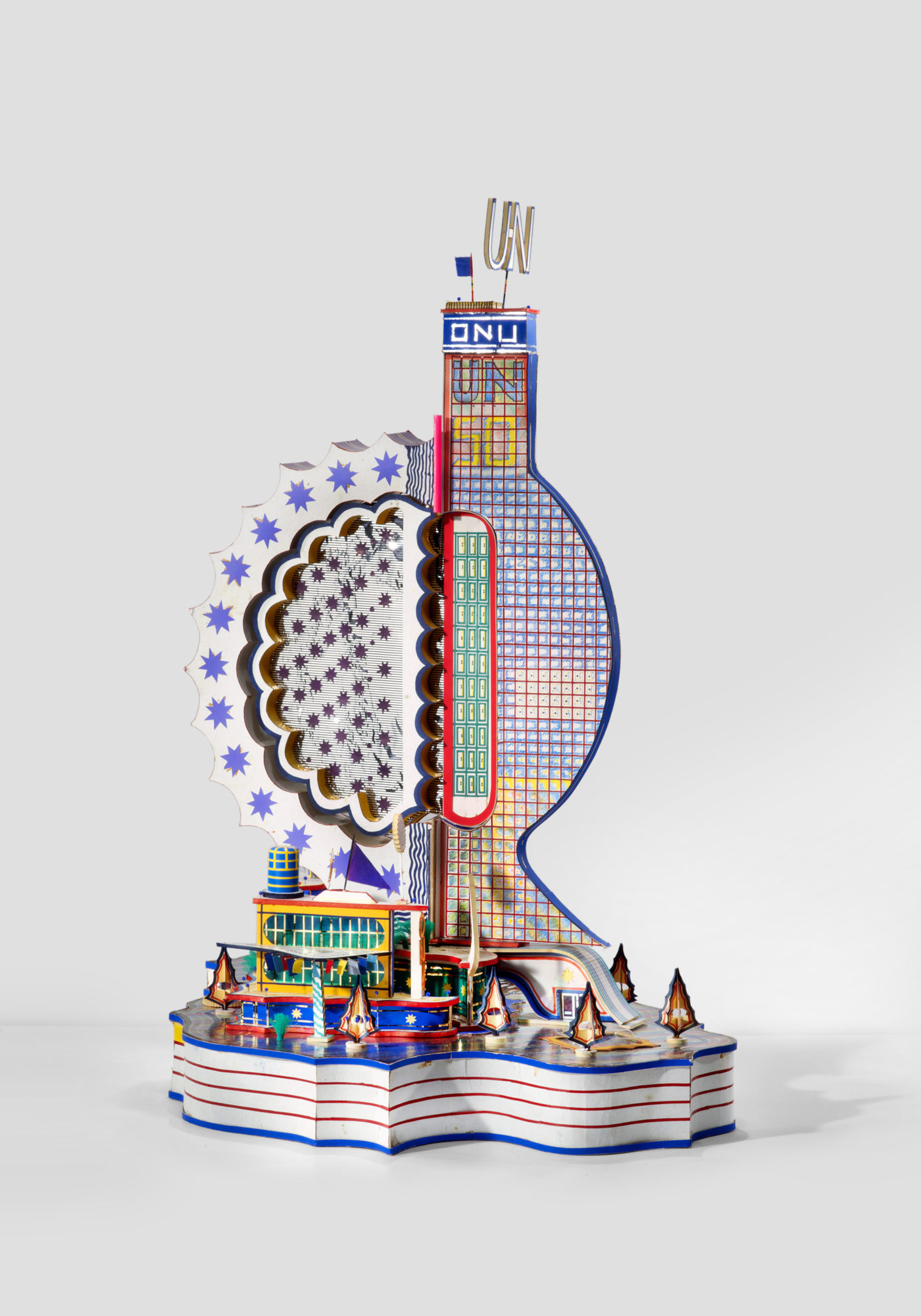

Bodys Isek Kingelez, U.N., 1995, installation detail, 35.81 x 29.12 x 20.87 irregular [courtesy of the artist and CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva and MoMA, New York]

Share:

“I am a designer, an architect, a sculptor, engineer, artist.” That’s how Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015), the subject of a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, once described himself. The show’s curator, Sarah Suzuki, proposes adding one more identity to the list: “a visionary,” Kingelez once explained, “is someone who dreams of what doesn’t exist yet.”

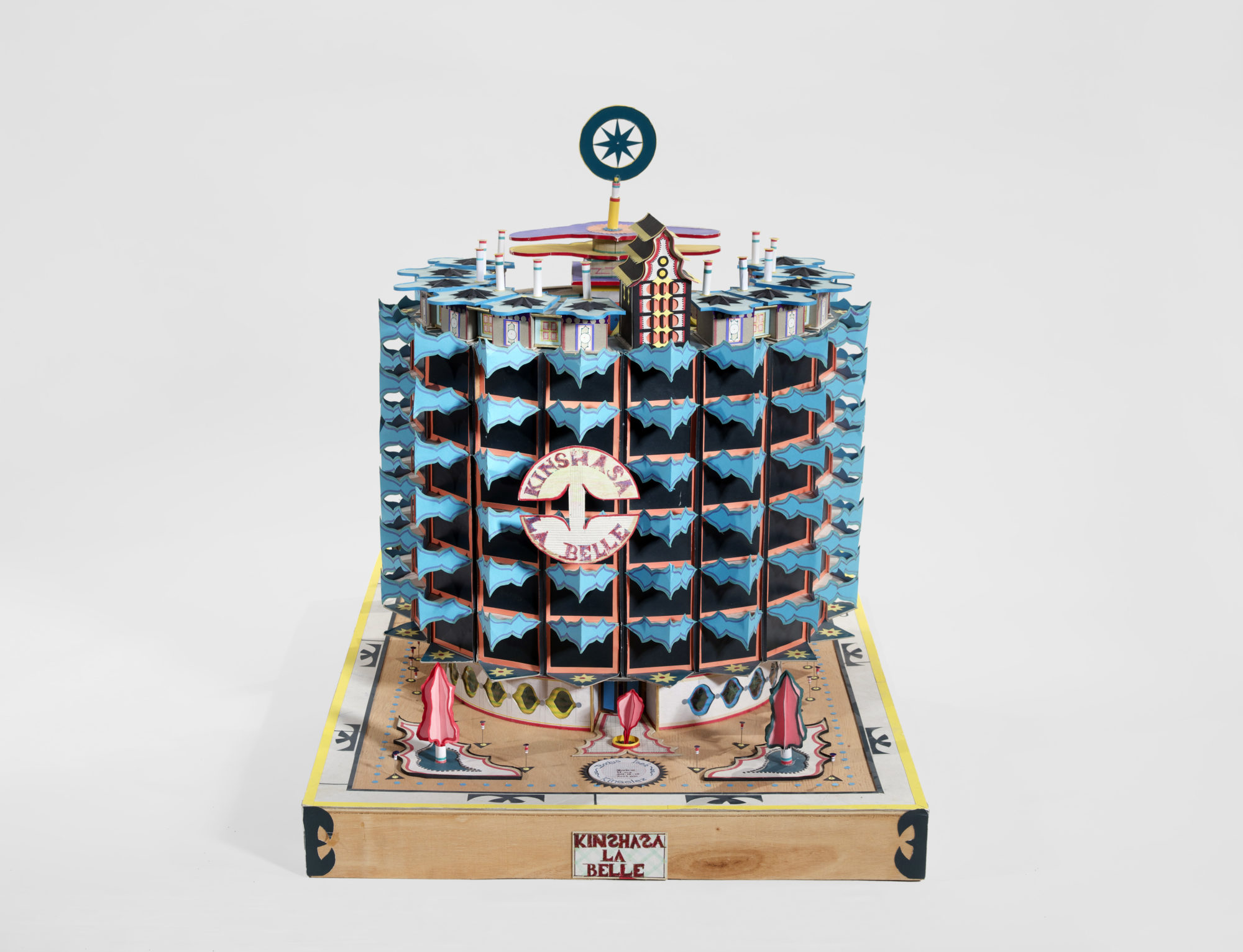

The self-taught Congolese artist confected elaborate and vibrant buildings and cities—what he called “extreme maquettes”—from paper and cardboard, mostly, but myriad other materials, as well. An omnibus list of media at the start of the show names everything from foil, pins, and beads to stickers, Styrofoam, and circuit-board diodes. In later works, consumer product packaging also features prominently, its graphics used decoratively or as large-scale advertisements. Kingelez dedicated his buildings to cities (Paris Nouvel, 1989), countries (Allemagne An 2000, 1988), companies (Canada Dry, 1991), civic infrastructure (Aéromode (Aéroport Moderne), 1991) and intergovernmental organizations (U.N., 1995).

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Kinshasa la Belle, 1991, paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 24.81 × 21.62 × 31.5 inches [photo: Maurice Aeschimann; courtesy of the artist and CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection and MoMA, New York]

In larger works the buildings combine into dense and dizzying cities. Some reimagine existing places, such as the rural village where Kingelez grew up before moving to the capital city of Kinshasa in 1970 (Kimbembele Ihunga, 1994). Others project future places, such as the fictive metropolis of a millennium hence (Ville de Sète 3009, 2000). There are more than 30 works in the show—almost a third of the artist’s known production, and more than have ever been shown in the United States. They appear on space-age, rounded white plinths; some works rotate slowly on turntables, and others are reflected in mirrors from above. The exhibition was designed in collaboration with artist Carsten Höller, who knew and exhibited Kingelez.

According to Kingelez, the titles came first, and then came the visions. He would bypass preparatory drawings to build straightaway in long, feverish bouts. God himself, Kingelez believed, was an artist, for painting the mountains and the forests. And Kingelez saw himself, by extension, as “a small god.” His own name, in different forms, appears all over the work, whether inscribed in gold medallions or blown up to billboard scale. Since his inclusion in a landmark 1989 show in Paris, Magiciens de la Terre, which sought to counter the art world’s entrenched Eurocentrism, his work has appeared in exhibitions around the world. Still, Kingelez was not well known in Kinshasa, where he spent his working life.

The level of handcraft in the works is astonishing. The building volumes are variously fan-shaped, fluted, or zig-zagging, and every surface is incised, collaged, or hand-colored. Craft, Kingelez believed, was a dying art, losing ground to the computer. A friend once encouraged him to take an early work to Kinshasa’s main museum. The staff there was incredulous that he had built it himself, challenged him to build another on the spot, and, when he did so, hired him as a conservator. He did that job for six years, working on traditional African art objects, before leaving to pursue his own art full-time.

But what, exactly, are these works? Not intended for building, they are more art than architecture, more sculpture than working model. Although the MoMA show appears in the cleared-out Phillip Johnson Galleries, formerly occupied by the Department of Architecture and Design, it is organized by the Department of Drawings and Prints. As Suzuki points out, the works are of, and on, paper. Though they aren’t proposals, they do embody propositions. Many monumentalize nations, and the idea of nationhood: Kingelez made Centrale Palestinienne (1994), for example, in admiration and hope, following the Oslo Accords. Responding to the scourge of AIDS in his country, he made works like The Scientific Center of Hospitalisation the SIDA (1991), and Industria da Pharmacia (1992), believing that centralizing scientific research would produce medical breakthroughs. The artist’s own tastes also shine through: He liked the flavor, color, and packaging of Primus, a Congolese beer, and so he dedicated a monument to it. But above all, these “city dreams,” as the exhibition title has it, are of a bright and distinctive urban future for a postcolonial African nation. Following almost a century of violent rule by Belgium, the Independent Republic of the Congo declared independence in 1960. Mobutu Sese Seko took power five years later and ruled the country he renamed Zaire as a dictator until 1997. Issues of self-rule, urbanization, and cultural authenticity, especially in built form, topped the national agenda during Kingelez’s formative years and working life.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, U.N., 1995, Paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 35.81 x 29.12 x 20.87 irreg. [photo: Maurice Aeschimann; courtesy of the artist and CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva and MoMA, New York]

Kingelez was a builder of worlds. And the MoMA exhibition couches his work, as he did, in utopian terms. Of Ville Fantôme (1996), for example, his largest and most exhibited city, the wall label quotes the artist: “There is no police force in this city … there are no soldiers to defend it, no doctors to heal the sick. It’s a peaceful city where everybody is free.” But there are also no people in the city. (The exhibition includes a virtual reality experience that allows visitors to enter the Ville Fantôme, a space not obviously meant to be inhabited.) Writing on the same work, curator Okwui Enwezor, who included Kingelez in his Johannesburg Biennale of 1997 and his documenta 11 of 2002, observes that it “signifies and communicates the unease we feel in dreams gone awry.” For him, the title (phantom city) “already denotes its depleted spatial character … a non-place. It is a space of anomie, temporally in the past, the bad dream of modernist planning schemes; in other words, a failure of imagination that time and again has plagued many such out-of-scale projects.”

For Enwezor, the work points up a familiar specter in sub-Saharan Africa, namely “the irrational, World Bank/International Monetary Fund-financed post-utopian vulgarism of corrupt African regimes.” Although it is called visionary architecture, Kingelez’s work is, in almost every case, eminently buildable: the models generally extrude a plan upward as stacked floorplates and tend to obey the laws of gravity. And indeed, works like his have been built. Enwezor writes that “Many African cities during the Cold War acted as a laboratory for urbanist and architectural ideologies of little interest in the everyday life of Africans.” “Paradoxically,” he adds, pointing to informal culture, “it is those parts of the city which receive very little governmental aid that have thrived and have produced what can be called an urban culture in the sense of making it a vital part of a city’s life.”

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Ville Fantôme, 1996, installation detail, 47.25 inches × 104.43 inches x 94.5 inches [courtesy of the artist and CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva and MoMA, New York]

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Ville de Sète 3009, 2000, installation detail, 31.5 × 118.12 × 82.68 inches [courtesy of the artist and Musée International des Arts Modestes (MIAM), Sète and MoMA, New York]

In her 2014 book, The Bright Continent, journalist Dayo Olopade uses the term “formality bias” to describe the error of well-meaning outsiders bent on aiding sub-Saharan Africa. Whether by preferring to work top-down and state-to-state, with corrupt or dysfunctional governments, or by grafting Western development standards onto places they don’t fit, outsiders miss successes on an informal level. Here, government failures have bred ingenuity, social cohesion, and informal institutions powered by kanju, a Yoruba word meaning something close to “hustle.” Olopade quotes a Nigerian organizer as saying, “What do we need local government for? I am local government.” Kingelez, in taking it upon himself to reinvent society, is also local government—as well as planner, architect, and builder. While one could find resonances with his work in everything from the Vegas Strip to global postmodernisms, the language is inimitably his own (and many of the raw ingredients could be found amid various architectural adventures in post-colonial Kinshasa). His personal vision is social in its concern for civic spaces and services (see Place de la Ville, 1993). But it is also formalizing: its strict plans remind Enwezor of the colonial imposition of the grid onto more organic existing developments; he cites Le Corbusier’s segregationist scheme for French Algiers—for which MoMA holds a 1935 drawing.

Although self-determined, the vision is also not necessarily one of self-determination. In reimagining the world, Kingelez reproduces existing states, mostly European great powers, and corporations, mostly Western. The first black African to have a solo show at MoMA, he holds a complex relationship with the colonizer. In a 2003 documentary shown in the adjacent gallery, Kingelez bemoans the neglect of the city’s Belgian-built core, which he considers its soul, and credits the country with his education in a Catholic mission. What Kingelez considered his gift to Belgium (Kinshasa la Belle, 1991) features a brise-soleil of abstracted butterflies, swarming the building as if at once to decorate and defend it.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Place de la Ville, 1993, paper, paperboard, and other various materials, 39.37 x 15.75 x 15.75 inches [courtesy of the artist and The Museum of Everything, and MoMA, New York]

The impression of these cities, which just about any visitor is likely to find transfixing, may therefore be one of both exuberance and ambivalence. The glossy metropolises evoke what theorist Keller Easterling calls “city porn,” or the growing genre of promotional videos showing rendered flythroughs of the free zones springing up across East Asia and the Gulf—places for capital rather than people. Olopade acknowledges the growing interest in building “special economic zones” in Africa. But she sees these visions of “starting over” and “glorifying the blank slate” as essentially pessimistic, another kind of formality bias.

The exhibition catalog is excellent. A slim volume, it nevertheless contains more on Kingelez than has been published in any language. In addition to an extensive background essay by Suzuki, it includes brief contributions by professor Chika Okeke-Agulu, architect David Adjaye, photographer Sammy Baloji, and an interview with curator André Magnin, who was instrumental in Kingelez’s rise to fame. Best of all is the photography—both sweeping views of the artist’s cities and closely cropped details of the work. These photographs transform the works from images into objects: In seeing process—guide marks in pencil, where the paper has been adhered—we can also appreciate how masterfully the works have been made. Because Kingelez’s work overwhelms, the detail shots help. At its base, for example, Nippon Tower (2005)—a late, more abstract work—is collaged with graphics of a fluorescent light bulb and a cow drinking milk adhered to its clear plastic skin, which has been meticulously scored to suggest x-bracing; it is also buttressed by a Smint-brand mint-dispensing box, its own kind of micro-architecture.

Leaving the museum, I step out into mostly monochrome midtown Manhattan. The city has never looked so dull.