Dread Scott: Beyond History

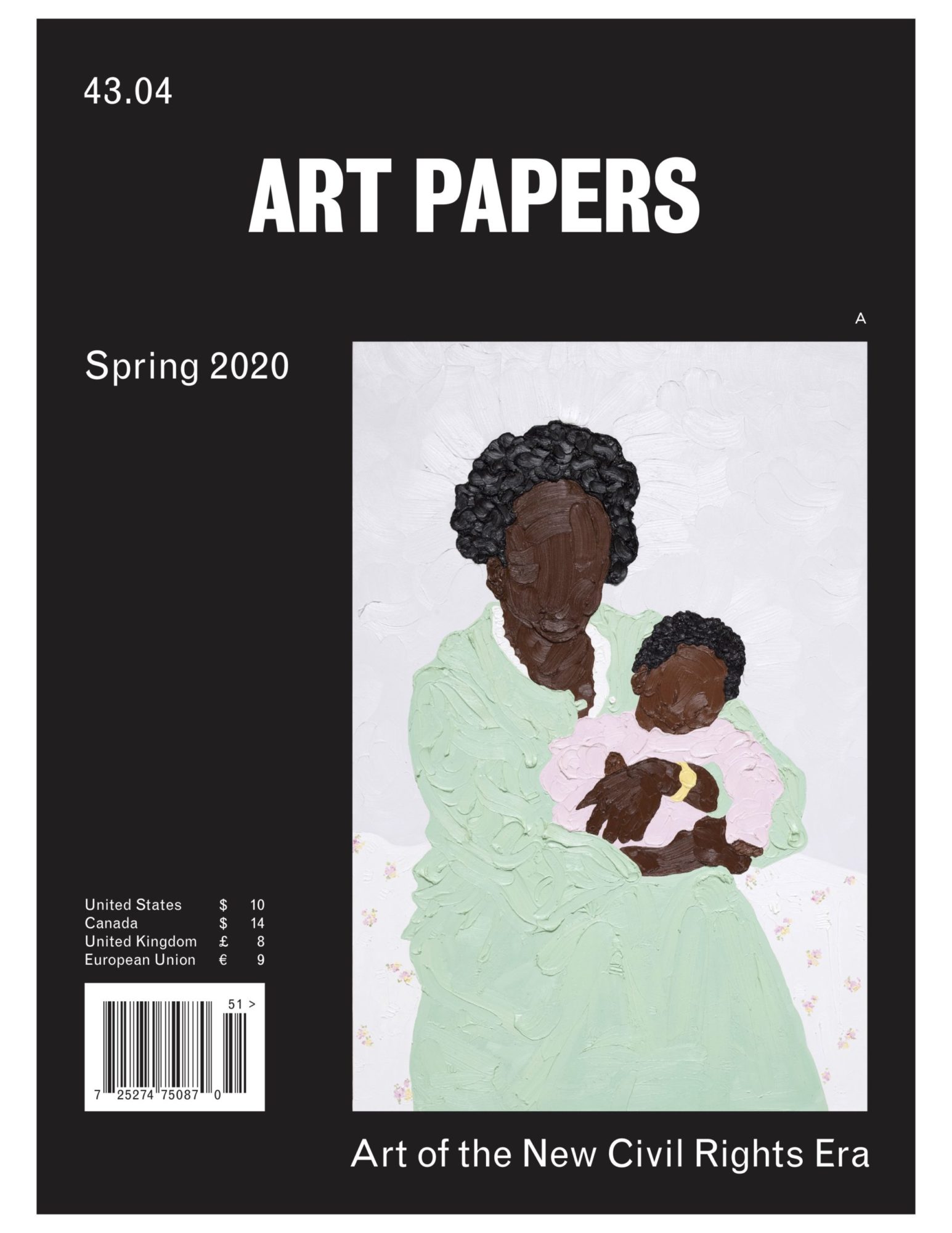

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

Share:

Until lions have historians, hunters will be the heroes.

—African proverb1

In New Orleans that week, the newspapers—The Louisiana Gazette, the Moniteur de la Louisiane, and the Ami des Lois—advertised embarkments bound for Liverpool, Philadelphia, and Baltimore upon ships with names such as Dolly, Ceres, and the George Washington. St. Philip Street Theatre announced the opening of plays, and a notice regarding some found strayed horses told how they could be reclaimed. There was even a hopeful note about a mislaid check that the owner thought someone might kindly return.2 The cost of commodities such as salt, tobacco, coffee, and whale oil were printed alongside notices of the sale of estates, lots of land, and sundry items, including: 30 boxes of brown soap, 8 bales of India cotton, 10 barrels of pepper, 30 cases of cider, 30 boxes of mould candles. This was early January, in the year 1811, and among the advertised merchandise—indigo, almonds, velvet corks, flint decanters, tin plates, calicoes, loaf sugar, Jamaican rum, window glass, and Havana segars [sic]—there were also human beings offered for purchase.

Some were named, including Sally, a woman being sold along with her two-year-old child.3 Many others were left unnamed, vaguely described in a notice for an auction “in the St. Charles Parish, including around 70 heads of slaves, of all ages and two sexes, of which among them are many with talents and very good subjects.”4 Aside from the callous treatment of humans as commodities that was blankly presented as business as usual, there was also an extraordinary event being chronicled in the papers that week—a slave revolt, what we now call the German Coast Uprising or the River Road Rebellion—and it caused widespread panic among the newspapers’ target audience.

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

Two centuries later, in November 2019, overtly political artist Dread Scott, who declares that his aim is to create “revolutionary art to propel history forward,” restaged this slave revolt.5 On the surface, the performance highlighted a little-known historical event. The act of live, performative commemoration brought together hundreds of participants dressed in period costume, some on horseback, who marched for two days along the River Road to New Orleans.6 A press release stated that the participants would be seen with their “flags flying, singing in Creole and English to African drumming.”7 Although shorthanded as a “re-enactment,” it was, much more than that, a commemoration of the historic event and an alternate history. This large-scale performance raises questions about our dependence upon a historical archive written by the slave-holder and uses the medium of collaborative performance to call into question the nature of agency.

The slave revolt effectively ended two days after it began, in a battle on the levee against 80 armed planters.8 But in Scott’s counternarrative, the rebels were rewritten as victorious in a sunset battle against uniformed militia on the Bonnet Carré Spillway. Revising the history, the march continued the following day and ultimately ended with a celebration in the Tremé, near the French Quarter, re-imagining the rebels as successfully reaching New Orleans.

In its finale the procession took a winding path through the streets, passing onlookers who tumbled out of the bars to see. People confused it for a parade or a protest, but most often for a movie shoot. Many tourists joined the march, which ultimately funneled into Congo Square, where burning sage was placed at the entrance to cleanse any bad intentions. It was there that the final phase of the performance began, what Dread Scott described as “a vibrant celebration of resistance and freedom,” which included music, dancing, an appearance by the Mardi Gras Indians, and a powerful poetry reading by Sunni Patterson.9 The last act made plain that the struggle for resistance and equality continues in the present day.

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

But if Scott’s event ended with a party to which everyone was invited, it didn’t begin that way. To my mind this aspect is its second major achievement. If the first is its nuanced dialogue with history as a text, the second concerns its use of the amorphous space of public performance as a placeholder for a difficult conversation about the role of complicity in perpetuating racial inequality. Both of these themes were supported by the event’s design, which drew lines of access, spectatorship, and participation that were alternatively flexible and rigid. The performance imitated the kind of secrecy, rumor, misinformation, and conspiracy involved in the actual slave revolt, raising the issue of who gets to control the historical narrative.10 But I found that the expansive borders of the performance also muddled the role of spectator and participant in a manner that concretized other abstractions. For example, the contagious spirit of rebellion was depicted in the final act’s invitation that spectators join the march. More poignantly, though, the reach of slavery and its continued contamination of our society were personified in moments when the performance was felt to be inescapable.

The march began in Laplace, LA, around 10 am on November 8, with a dramatization of the initial revolt on the Andry Plantation. Few had advanced knowledge of this first act, and the audience comprised members of the media who received press packets, schoolchildren, neighbors notified by the city, and some others who heard by word of mouth. Told where to stand in order to be in compliance with the permits, we watched the costumed re-enactors perform a scene representing the events of January 8, 1811, in which enslaved persons attacked their master, raided his storehouse for weapons, and began the march toward New Orleans. A white man playing the plantation owner shouted from the porch of the old house, “Why are you doing this? Haven’t I been a master who treated you with love and understanding?” The group declared its self-emancipation: a woman yelled, “We are free now!” They attacked the plantation owner before running to the back of the house. Spectators could then hear—but, importantly, not see—another scene of revolt in action. After a moment the procession reappeared, marching in a formation that included men on horseback and scores of people holding machetes, scythes, and other weapons. The rebels chanted: “We’re going to end slavery,” “Join us,” “Freedom or death,” and “On to New Orleans.” Neighbors came out of their homes to watch the procession. I spoke to a pair of them. A woman said that she thought it was “wonderful for this generation to know about this history,” and her neighbor said flatly that it was “a good way to screw up a Friday morning.” One presumes he was referring to the traffic.

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

Dread Scott’s performance obstructed the commute at various points on its 26-mile, two-day journey from the outlying areas of New Orleans to Congo Square. In doing so, it evoked the Situationist International’s goal of interrupting the smooth flow of the everyday. This objective is a laudable one, especially insofar as it traces a through-line from slavery to present-day capitalism. However, some critics lambasted Scott’s inattention to the working man’s precarity (as in, his need to be at work on time) in designing this feature of the performance: cars were halted in Laplace, where the re-enactment began, and at other points. One of the fascinating things about this type of performance is the way it foists a role upon unwilling nonparticipants, who may find themselves sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic at 11 am on a Friday. This occurrence was one of the many ways that Scott orchestrated a commentary upon agency, control, and access: the work stratified spectatorship and participation into several different levels in a manner that underlined the expansive reach of the historic event at the same time that it dramatized the access and control of the historic narrative.

In his book on the 1811 revolt, American Uprising, Daniel Rasmussen notes that, in the early hours after the initial rebellion, slaveholders “heard about the revolt just as many newly minted insurgents had—through the grapevine of news and information that coursed through the slave quarters”—that is, from enslaved people who made a calculation to betray the rebellion.11 Rasmussen also stresses the likely use of “slave spies” and a Kongolese war strategy of doubling back “to confuse the enemy.”12 In short, obtaining and controlling information was of paramount concern to the renegade slave army, and this aspect, too, became a feature of Scott’s collaborative performance.

The precise route the performers would take was a closely guarded secret. So that the media could be present to document the performance, a packet was circulated with five designated “viewing points,” but the email that shared locations emphasized confidentiality.13 A local newspaper that previewed the event stated, “Due to concerns about event safety, information about the route was not posted in advance … recommended viewing sites will be posted on the project website this week.”14 Delivering upon this promise, just a couple of days before the performance, the website nola.com listed three possible viewing spots available to the general public—what in the press packet were listed as viewing spots 3, 4, and 5.15 However, there were some nonmedia and nonstaff present at viewings 1 and 2, which were not advertised in advance. Everyone with whom I spoke who fell into this category said they had heard via word of mouth, from a friend who was in the re-enactment, or an acquaintance who had given permission for the performance to use their land.

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

The event fostered a stratification of audience members with varying levels of access: there were media, given advance notice of five designated viewing areas; and the general public, officially invited to three; but there were also those who knew someone with inside intel. People in the last category often had the best information, and I’ll note briefly here that some of the digital pins shared with the media were incorrect. I found myself wandering in the cold at dusk on the Spillway and had to collaborate with other lost journalists to find the correct location of the battle scene. Rather than interpreting this confusion as an organizational gaffe, I saw it as an apt portrait of how information flowed or was contained during the historic slave rebellion, spreading to some by word of mouth, withheld from others by secrecy and misinformation. In that moment, and at other times, I was aware of the sands shifting beneath my feet, and instead of being merely a spectator, I found myself playing a role in the performance.

In the gift shop of the Destrehan Plantation—one of the area’s preserved, tourable, historic landmarks—the shopkeeper and a handful of customers were trading information about the re-enactment. A local woman said that she heard about it from the sheriff’s office. The shopkeeper confirmed, for some out-of-towners, that the performance would pass by the plantation the following day but denied that Destrehan was officially involved. Someone raised a rumor that the re-enactors were to spend the night in tents on that very plantation. The shopkeeper refuted this statement; she heard that they would spend the night at the Catholic church in Norco. This exchange had none of the tension or stakes that the rebellion would have produced, but I was aware of an eerie parallel. As I stood there in the gift shop, with its general store ambiance, on a plantation that was attacked by the rebel army in 1811, I found myself unwillingly re-enacting a role in the drama, though it wasn’t one included in our media packets: that of townsperson, listening to rumors of the army’s progress up the River Road.

Many miles distant from the march, I felt myself nonetheless drawn into the performance’s orbit, on an invisible periphery—the outermost ripple made by a pebble dropped into a pool. This common feature of public performance took on new meaning in a work about slave rebellion, for it resonates not only with the theme of how information was passed and contained in the historic event but also suggests the delicate boundary between spectator and participant, agent and object, passivity and complicity.

Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a performance initiated by Dread Scott outside New Orleans, 2019 [photo: Soul Brother; courtesy of Antenna Works]

If a person bought calico, sugar loaf, indigo, rum, or cigars in January, 1811, they were playing a part in the institution of slavery, whether intentionally or not. Similarly, if you were in the right part of the French Quarter on Saturday, November 9, 2019, you were playing a part in Scott’s performance, whether you merely sensed the vibration of drums in the distance; gazed bemusedly at an odd parade before turning back to the game; or, catching the spirit of rebellion, joined and marched along. Scott crafted a performance that, through the strict regimentation of access, spectatorship, and participation, highlighted agency as a central issue, even as it stressed the difficulty of apprehending history from the records written by the oppressor.

In the newspapers which covered the rebellion that week in 1811, the rebel slaves are called “brigands” or “fugitives” or “banditti,” presumably thought of as thieves for stealing themselves from the landowners. With its readership still reeling from the revolt, the Moniteur of January 12, 1811, counseled citizens to stay vigilant, issued calls for patrols, announced a curfew of 6 pm for all “male negros” (which we might assume included free men of color), and related the closing of the cabarets for the sake of the “public security.” Obviously, the “public security” did not include that of the plantations’ workforce; nor did it take into consideration the well-being of Sally, who was being sold with her two-year old that week, or the 70 other unnamed persons who appear for sale in the same issue of the newspaper.16

Most simply stated, Scott’s collaborative performance probed the limits of our own historical records, presenting a moveable narrative that related the events from the side that did not write the history books. In doing so, he has not merely rewritten history, he has written a more complex history of the 1811 slave rebellion and its participants, in the broadest sense of the term. It is a history best rendered in the form of a collaborative, communal performance, for it cannot be contained by the margins of the page.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2020 // Art of the New Civil Rights Era.

Sarah Juliet Lauro is assistant professor of hemispheric literature in the Department of English and Writing at the University of Tampa. She is the author of many academic articles, editor of the journal Studies in the Fantastic, and the author of a book that addresses the folkloric roots of the living dead, The Transatlantic Zombie: Slavery, Rebellion, and Living Death (Rutgers University Press, 2015). Her next book project turns from zombies as figurations of slavery and slave revolt—her central interest in these monsters—to commemorations of slave rebellion in literature, art, film, and digital culture.

References

| ↑1 | A photograph of these words graffitied on a former slave fort in Ghana can be seen in Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum, the Memphis museum dedicated to the history of fugitive slaves. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Louisiana Gazette, January 19, 1811. |

| ↑3 | L’Ami des Lois, January 15, 1811. |

| ↑4 | Moniteur de la Louisiane, January 12, 1811, author’s translation. |

| ↑5 | Antenna, “Large-Scale Performance to Reenact Biggest Rebellion of Enslaved People in U.S. History,” press release, October 7, 2019. |

| ↑6 | Tallies of participants vary. One article estimated that 400 people took part: Oliver Laughland, “‘It makes it real’: hundreds march to re-enact 1811 Louisiana slave rebellion,” The Guardian, November 11, 2019, web; another put the actual number at closer to 300: Katy Reckdahl, “‘Heartbreaking’ but ‘Empowering:’ Re-enactors Recall Doomed 1811 Revolt,” November 9, 2019, web. |

| ↑7 | Antenna, press release, October 7, 2019. |

| ↑8 | Daniel Rasmussen, American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 136. |

| ↑9 | Antenna, “Community-Engaged Art Performance, Reenacting Largest Rebellion of Enslaved People in U.S. History, to Culminate in New Orleans’ Congo Square,” press release, November 5, 2019. |

| ↑10 | The artist’s statement on the project’s website acknowledges that the clandestine nature of slave revolts was mirrored in the event’s organization of small groups to plan the event. Slave Revolt Reenactment, About, web. |

| ↑11 | Rasmussen, 104. |

| ↑12 | Rasmussen, 129–130. |

| ↑13 | “Please note that this information is highly confidential. We ask that you do not share outside of your team,” personal communication, email of November 6, 2019. |

| ↑14 | Will Coviello, “The Road to Freedom,” Gambit 40, no. 45, November 5–11, 2019. |

| ↑15 | Doug MacCash, “1811 Slave Rebellion Re-enactment Starts Friday: Where and When to See March,” nola.com, November 16, 2019, web. |

| ↑16 | Moniteur de la Louisiane, January 12, 1811. |