All images: Marisa J. Futernick

Grits

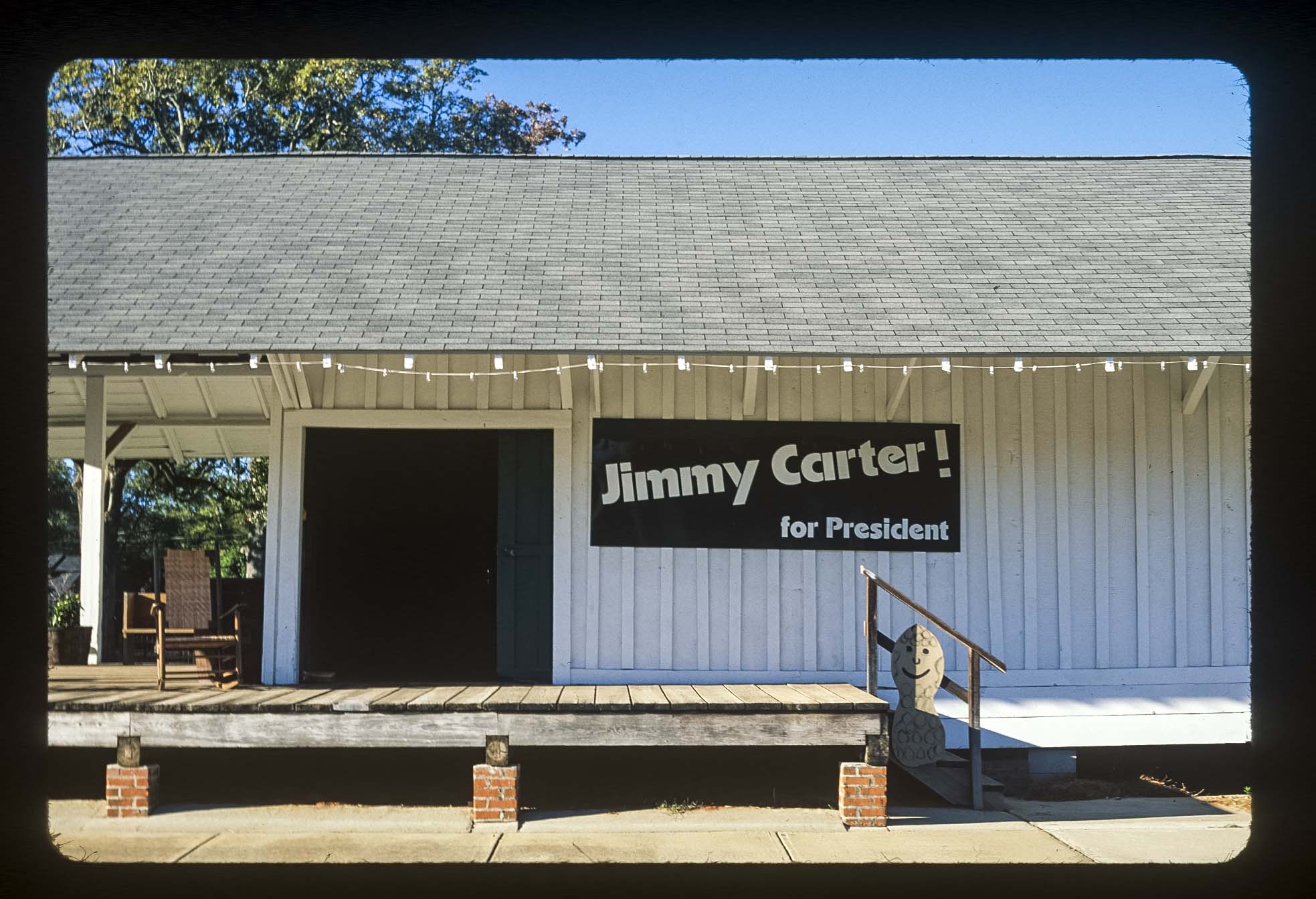

Marisa J. Futernick recently undertook a cross-country road trip to visit all 13 of the nation's presidential libraries. The goal was to acquire materials for an artist's book to be published in advance of the 2016 US presidential election, combining photographs from the journey with short stories. Mixing historical fact with fictional projection, the writings cast presidents from Herbert Hoover to George W. Bush as characters. The accompanying photographs are shot on analogue film, making them difficult to date, and bringing everyday details of the presidents' lives—from their hometowns and childhoods to their final resting places—into the consciousness of the present day. Like her texts, Futernick's images combine to create American portraits that are as historically unreliable as they are culturally true.

Share:

I pulled out the big cast-iron stockpot and placed it on top of the stove. I switched on the overhead light. “Did you already put some oil in the pan, darlin’?” Rosalynn asked. I poured in a big glug of olive oil. She slid in the chopped carrots, celery, and onions off the heavy wooden cutting board—the teak one that I made for her as a Valentine’s Day present last year. The sweet smell of frying onions filled the kitchen. It made me hungry. Rosalynn and I eat a lot of soups now. We try to eat healthy.

“Honey, remember how you used to cook up two big, fat steaks, and put a nice pat of butter on top of each one?”

“Sure, Jimmy. But that was only for a special occasion, like for your birthday or somethin’. We didn’t eat that way every day, you know.”

No, I suppose we didn’t eat steak much back then, but not because we were health conscious. We ate what was cheap: grits, cornbread, eggs; maybe a Brunswick stew if we were lucky, filled out with a lot of corn and okra, and not all that much pork. (Though we never put any possum in ours, like some folks did.) There was chicken and dumplings on a Sunday, if it was a good week. Peaches and pecans, from the farms and yards of friends and neighbors, were always a treat. And peanut pie, if someone had some extra crop going. But mainly, we just ate a whole lot of grits: grits with butter and salt, grits baked with cheese, grits topped with a few chunks of ham and a little redeye gravy.

I remember eating grits just about every day in that first apartment that we had, over on Paschal Street: Public Housing Unit number 9A. Poor Rosa, marrying a man who couldn’t even put a real roof over her head. We were awful grateful to have that apartment, though. Being helped out when we really needed it—we never forgot what that meant.

It’s still there, that little red brick unit. It has a tidy yard out front, with a few shrubs, and a white hydrangea in a big plastic pot. We drive past it on our way to church every Sunday. It sits across from the park where the campaign staff and I used to play softball, and where I played ball with each of our three boys when they were young. (Amy has never been much interested in softball.) So now I’m waiting for our grandkids to take up the game. Little Jason is already six, and loves to play catch. We throw the ball back and forth, right on the same patch of grass where my brother Billy and I used to play when we were growing up.

I sure wish that Billy still ran his service station here in town. It made me happy to see him every time we stopped in for a fill-up: his flushed, pudgy cheeks and sideburns poking out of a bright yellow cap; his denim overalls, always a little too tight around the belly and a little too saggy in the bottom, bless him. When he smiled, his eyes squinted closed behind thick, black-rimmed glasses, and he flashed a strip of glowingly white upper teeth. That grin just made you feel that everything was easy, as though the world didn’t exist outside of our own little town of Plains, Georgia. It was a good feeling. We used to put thin sheets of mesh over the peanut plants to protect them from pests, but there was no netting covering Plains. So, when the outside world eventually swarmed in, it stung like yellow jackets.

When Billy came to the White House for dinner after the election, he acted as if someone had died. “It’s okay,” I told him. “It’s only an election.”

As it turned out, it was hard to come home. It must’ve been that way for Rosa, too, that first time we had to come back to Plains, when Daddy got sick and we moved into that public housing unit. She thought she’d blown this town for good. I used to think that she only agreed to marry me because I was in the Navy, and she thought I was her ticket out of here. I was, for a bit: we had a few exotic years moving from Virginia, to Hawaii, to Connecticut, and finally to California, before our sudden return to Plains to take over the family business.

As if Rosa knew what I was thinking, she said, in that warm, gentle voice of hers, “I’m glad we’re home now, Jimmy. I think it’s better this way.” She didn’t look up from the chopping board as she said it. She just kept on peeling potatoes, her hands wet and red. I gave her a kiss on the forehead, gathered up the peelings, and threw them into the trash.

When the Iran hostages were released, right smack on Inauguration Day, well, I just could not believe it. The timing—it was as if Reagan had arranged it personally, like it was part of his script all along. But we were the ones who got them out, and once the hostages were headed home, so were we. The next day, I gave a press conference. Standing at a podium, in a beige raincoat that was hardly enough protection for the chill of that January morning, I told the country what I had been praying to be able to say for 444 days: “They are no longer prisoners; they are, indeed, free.” But by the time I spoke those words, I was not the president anymore. I was just a man.

We did most of the packing ourselves on our way out of Washington—we never much got used to other people doing things for us, even though we’d had four years of it. (We cooked dinner for ourselves every Sunday, too.) Amy put her favorite stuffed animals, plus a few of the cat’s toys, into a brown cardboard moving box, and wrote “IMPORTANT STUFF!” on the outside in giant letters, so that it would be one of the first to be unloaded when we got back to Georgia. Rosa and I packed a few necessities into the white vinyl gym bag we got at the Lake Placid Olympics—just enough to tide us over until the movers arrived with the rest of our things.

Amy already misses the tree house that I built for her on the White House’s South Lawn. I promised her that I would build an even bigger one in Plains, just as soon as I have a chance to get the lumber together. “You’ll help me design it,” I told her, “and it can even have two floors, if you’d like.” Her blue eyes widened behind her glasses. “A tree house with two floors?” She couldn’t believe it was possible.

It was a mild early spring day, but I felt a chill on my skin. I put on a cardigan that was hanging on the back of the kitchen door—the same one I wore for that televised “fireside chat” I did in ’77. Gerald Ford used to make fun of me for giving speeches in cardigans. “The man looks more like Mister Rogers than President of the United States,” he had told the press. At the time, I thought he was bitter about losing to me in ’76, but I like Jerry now. He’s a good man who was given a rotten job—one he hadn’t even asked for, like Truman and Johnson before him.

Jerry and I write to each other often these days. He called me up the morning after I lost the election to ask if I’d like to golf sometime. “Make it softball,” I said, “and I’ll be there.” In the end, we went swimming. We lay back on lounge chairs, side by side in our bare chests and trunks, and had orange Popsicles—they were as close as you could get to the Frosted Orange at the Varsity without having to go to Atlanta. When I was governor there, if I was working late, I might pick up some fried peach pie from the drive-in, and maybe a Frosted Orange, too; I mostly just liked hearing the kids working there shout the Varsity slogan: “What’ll ya have? What’ll ya have?”

“Do you honestly wish you had another four years, Jimmy?” Jerry asked. I thought about it for some time, and as my Popsicle melted and I stared into the clear swimming pool, I noticed how much more relaxed Jerry seemed nowadays. “I just wish it had been someone else, that’s all,” I said.

Rosa and I were taking turns stirring the soup. I opened a pack of boiled peanuts and started to crack into one. She shot me a disapproving look. “Jewish people call it ‘noshing,’” I explained, as if that justified my snacking. Rosa turned the burner down to low and switched on the little kitchen TV. I could hear Reagan’s voice—raspy and insincere—but I couldn’t see his face, with the sun reflecting off the screen. I angled the TV toward the stove, and there he was. His skin looked strange, as if it was made from stretched Silly Putty. And all that hair pomade was just ridiculous. Sometimes, I started to laugh about it all, but then I would remember that this man was now President of the United States.

I put my hand around Rosa’s waist. “Let’s go square dancing. How about it?”

“Aw, Jimmy, I think our square dancin’ days might be over, don’t you?”

“We can do things like that now. And we have a certificate in square dancing,” I reminded her, which was true. “I think we owe it to ourselves to take it up again. You should dig out your hula hoop, too—you used to be so good at that—and I’m gonna find my old ukulele from Honolulu, and start playing again.”

It didn’t take me long to find it in the hall closet, and I started to strum, trying to remember any little ditty. I heard the voice of Frank Reynolds, the newscaster on ABC, and he was talking about Lyn Nofziger, who was the president’s advisor for political affairs. “Lyn Nofziger has told reporters at the hospital that the president was not wounded,” he said, then urgently continued: “Wait …. He was …. The president was hit?”

That’s when the set lost its signal, and all we got was static. I pounded the top of it with the side of my fist. I could see men in three-piece suits and trench coats on screen through the fuzz, one pointing an Uzi sharply up toward the sky; I recognized the Florida Avenue entrance of the Washington Hilton, not far from the White House. Reynolds was frantic and yelling. “The president was hit …. He was hit in the left chest.” Rosa leaned against me, the back of her hand covering her mouth.

I poured two tall glasses of lemonade. I left one on the counter for Rosa, and took mine out through the screen door, to the side porch. I sat on the freshly repainted swing. Rosa followed me out, and we rocked, slowly, as the unattended soup boiled over on the stove.

There is still a green and white bumper sticker on Billy’s truck from the campaign. “I told y’all to use red, white, and blue,” Billy said. “Always red, white, and blue for an American campaign.” We used green and white for everything. Everyone said that it was crazy, but I liked the green and white. It was new, and it meant that we were going to do things differently, better, and more honestly. We were going to move away from the old American fantasy that we could indulge and consume forever, without consequence or effort. We were going to look to the good, simple things that came from hard work; to the dreams within reach.

Out on the porch with Rosa, I could smell the damp soil of the surrounding farmland, drifting through the sweet afternoon breeze, and faintly hear the emergency newscast coming from the TV inside. Events in Washington had interrupted One Life to Live. My mama, a big soap opera fan, would not be happy.

The man was resilient; you had to give him that. Thirteen days after an assassination attempt, he was back at work in the White House, as if nothing had happened.

The summer came, and the summer went. If I wanted to, I could have slept until 10. I could have had a glass of wine in the middle of the afternoon. But I was an early riser, and I never much had a taste for alcohol. Even on the night I launched my candidacy, in a bar—good old Manuel’s Tavern, in Atlanta—I only had a few sips of beer. I had always been a stickler for productivity, and punctuality. Rosa teased me for it. “Everyone always has to be ready early for you, huh, Jimmy?”

“I just don’t like to waste any time, that’s all. There’s too much to get done.”

And now we had all of this time. I did the laundry. I read, mostly poetry: Dylan Thomas, Robert Frost. I worked out back in the shop, where the air smelled of cedar and birch, and I felt calm and useful. Late in the day, when the sun was low, I liked to wander across town to the old family farm, where the whitewashed house where I grew up still stood. As harvest season came, and thousands of dots of cotton glowed pinkish gold in the evening light, I took off my socks and shoes and walked barefoot out into the fields, feeling the cool earth between my toes, like when I was a boy. Sometimes I would pull a bud from one of the plants and it would prick my finger and make me bleed onto the little white ball of fluff.

In October, something came in the mail. “Darlin’, there’s a letter here for you from the White House.” Rosa handed me a thick, crisp envelope with the familiar blue embossing on the back.

“He wants me to fly to Cairo with Jerry and Dick, for Anwar’s funeral,” I told her. Anwar Sadat’s assassins had been more successful than Reagan’s. The Egyptian president was at a parade and thought the killers were part of the ceremony as they approached the grandstand. So he stood saluting them as they flung three grenades and emptied their AK-47s into his torso.

Reagan had decided not to attend the funeral himself, and to send the three ex-presidents in his place. As if we would get a kick out of being on Air Force One again, for old times’ sake. (And as if we had forgotten that it’s only officially Air Force One when the current president is aboard.)

As the most senior of the three of us, we let Dick have first pick of the seats. He looked formal and uncomfortable in his dark suit, as he silently took his place, and, with liver-spotted hands, picked up one of the glass jars of rainbow-colored jellybeans that were dotted around the cabin. “Is this a presidential envoy, or a goddamn children’s birthday party?” he muttered.

Jerry exhaled deeply and audibly through his nostrils. I don’t think he could ever forgive Dick for lying to him about Watergate, and I could never forgive Dick for lying to the American people. But here we all were, in the same Boeing 707. “Things are different now,” Jerry said, and I knew what he meant.

As we took off, I thought about Rosa making dinner back in Plains, and Amy playing in her tree house, and about how soon they would sit in the quiet of the evening to eat and talk together. I wrote them an Air Force One souvenir postcard: it had an oversaturated color photograph of the airplane on the front, and the official presidential seal on the back. “Maybe being unemployed isn’t so bad, after all. Love, Jimmy.”

Marisa J. Futernick is an American artist based in London. She has exhibited at such venues as the Whitechapel Gallery, London; Outpost, Norwich, UK; Morton House, Mexico City; Yale University, New Haven, CT; and BolteLange, Zurich. Her recent artist’s book projects include an edition co-published by the Royal Academy of Arts, and she was a 2014Ð2015 recipient of the Deutsche Bank Award.