Looking for Black Art in Baltimore

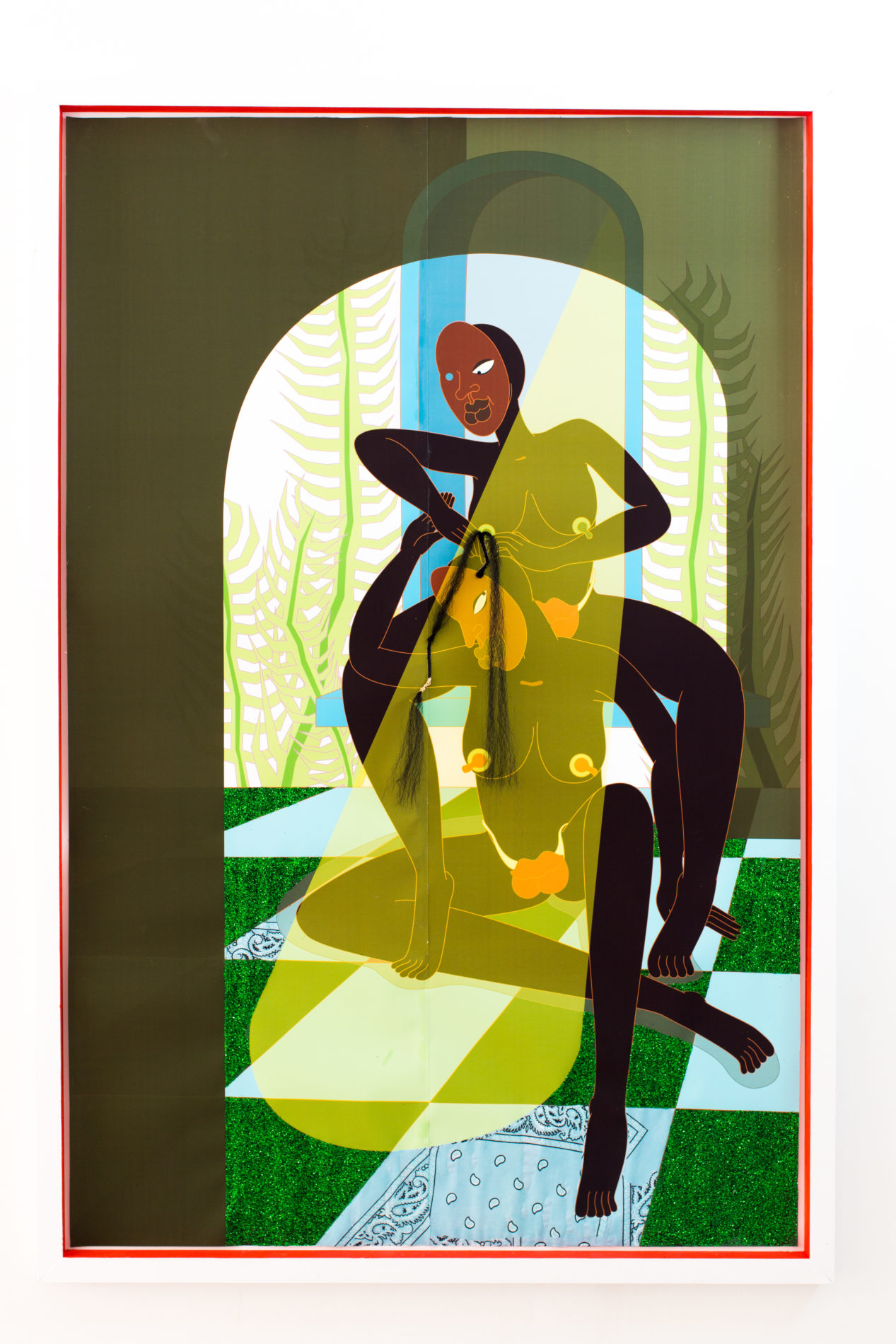

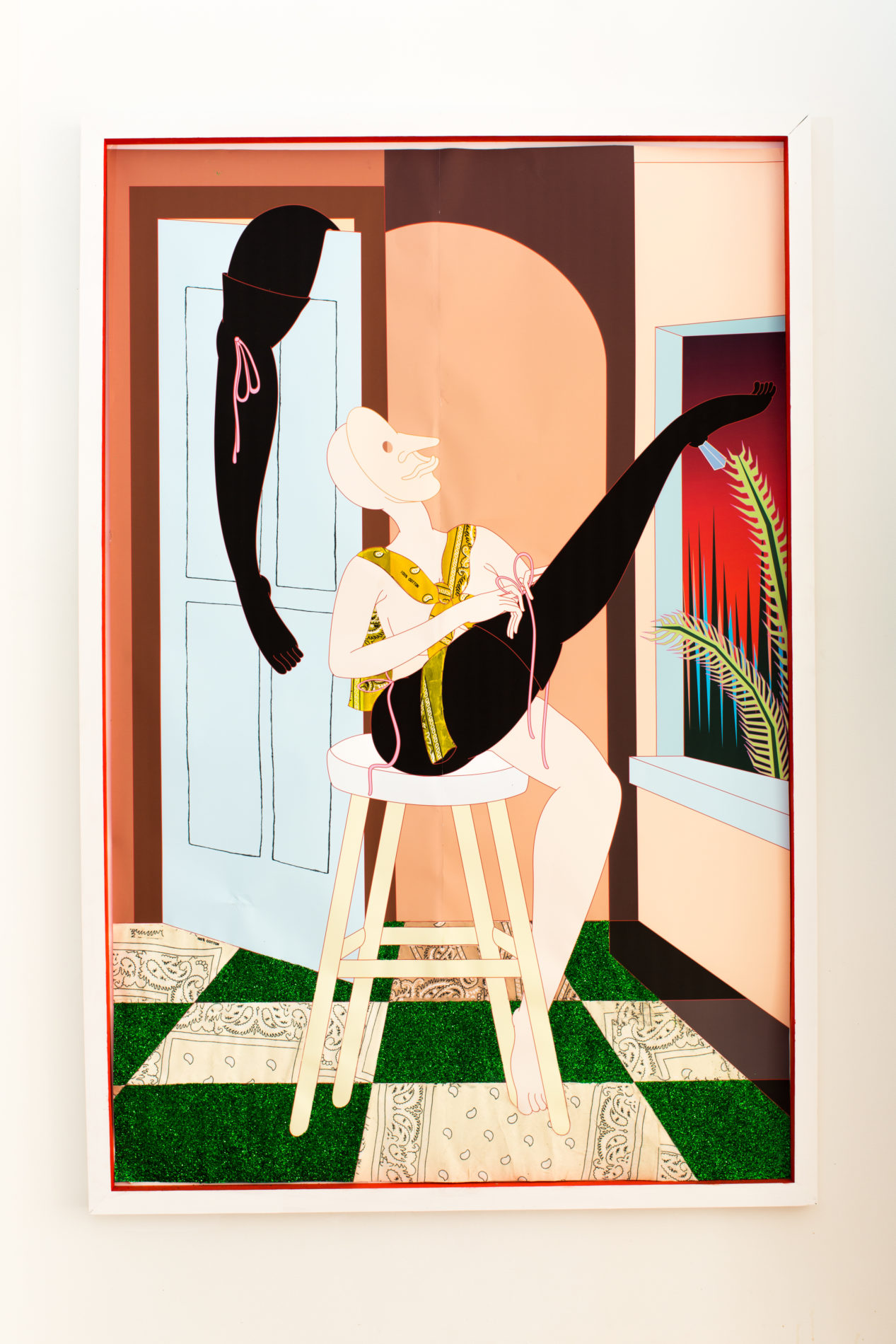

Theresa Chromati, Black Blissful Worship, 2016, collaged works on paper, digital, bandana fabric, glitter, 40 x 100 inches [photo: Justin Tsucalas; courtesy of the artist and Platform Gallery, Baltimore]

Baltimore is a black city. Its culture speaks for itself—from the golden days of the Royal Theater to what I know to be Lexington Market to the legacy of Baltimore club music, this city's whole essence is submerged by blackness.

Share:

Last year’s Baltimore Uprising was a boiled up reaction to the oppression of black people in Baltimore provoked not only by police cruelty, but also by the deprivation of necessary life resources that the city is infamous for never seeming able to take care of. Meantime we see an influx of movements, pioneered by institutions or even academic art depositories, invading black and brown communities in the city and being allocated spaces to start anything, from white-owned galleries to comic book stores, in unused buildings that have existed in Baltimore since forever and that we thought would never be filled. Being a Baltimore native who decided to start doing music I immediately began to notice the channels of oppression for black creatives. There seems to be limited space for black music in Baltimore that helps inspire some sort of promise, but there are no outlets for black visual and performance artists. Those black-owned creative spaces that do exist, being the rarities they that are, can’t alone take on the challenge of servicing the void of black arts in Baltimore. Most of the galleries here that are centrally enough located to be accessible are owned and dictated by whiteness. There are no savvy publications giving platforms to black artists; the one that does exist is obviously run by a white person. To really become known as a black visual artist, I would have no choice but to leave and go to NYC or DC, as many have already done.

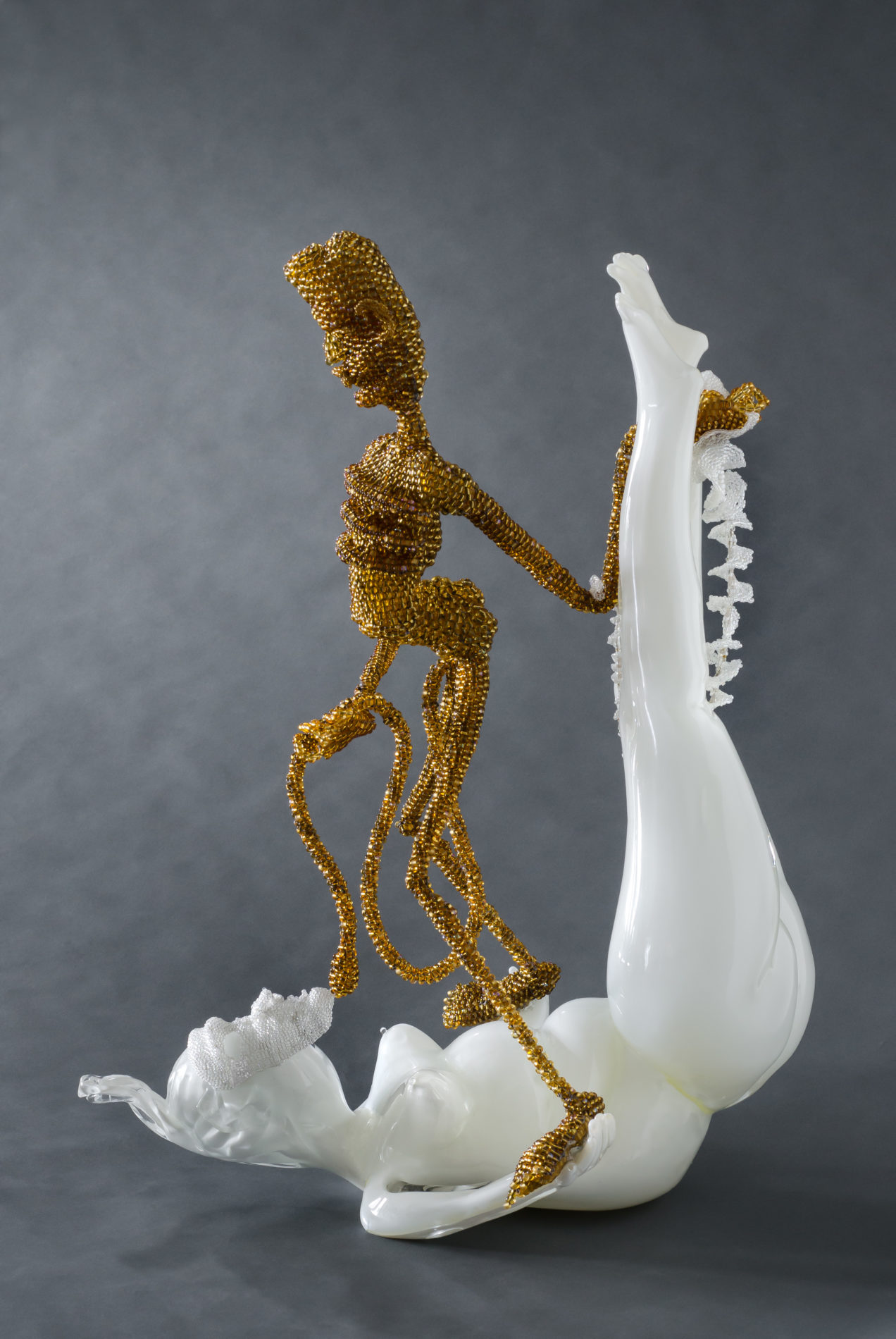

Joyce J. Scott, Lewd II, 2013, hand-blown Murano glass processes with beads, wire and thread, 22 ½ x 14 x 16 inches [courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, Baltimore]

Joyce J. Scott, Head Shot, 2008, seedbeads, threads, glass and bullets, 18 ½ x 4 ½ x 4½ inches [courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, Baltimore]

“You always have to be a prophet outside of your own land. I established my reputation long before I really had a gallery here in Baltimore support my work. I’m 67, I’ve been really making [work] since the 70s,” said Joyce after I told her that, for me, as a musician, I felt like I didn’t get support from my city until I treaded to other cities to slay and gain respect. Often artists like me feel as though support systems—beyond economics, from getting encouragement from peers to finding mentors—are nonexistent.

Joyce herself went straight to Mexico to study and find more affirmation for her aesthetic after she graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1970. “The art world is different in many ways. At least how you enter the world. When I got out of school I just literally started looking for stuff to do. I would go anywhere art related to look for work and exhibitions. At that time, everything was free, but now it’s an application fee for everything and that makes a difference. I was really rigorous and vigorous about my hunger. I was very hungry for work, very hungry to understand what art was like.” Joyce knew she had to leave to find a “piece of pie,” as she would say.

“I think that Baltimore is also a city that can engender great love if you’re a Baltimorean, but it can also make people angry. I mean, you’re in my neighborhood now, and you can see how easy it is to be a have-not here and remain that way. You just have to be vigilant. Like I said, I didn’t stay here and look for everything ’cause I knew there was more of a world out there waiting. But this is a city that has a population that’s had real trouble getting recognized, and their needs served, so it can be even intergenerational. What happens when you’re one of those children … who’s ready to fly? So, you see a lot of people running off, which I applaud.”

Joyce J. Scott, War Baby, 2014 hand-blown Murano glass processe with beads, wire and thread, 14 ½ x 18 x 15 inches [courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, Baltimore]

I’ve been asked why don’t I go, but I feel like I would be leaving myself. This is where I came from.

-Joyce J. Scott

But Joyce came back. She felt a need to be back in her community and be one of those who returned to her village. After graduating in Mexico she traveled the world, but she ended up back in Baltimore. “I was raised a lot of the time in Sandtown,” she says. “These was neighborhoods where you lived, of working class blacks. There were dentists, doctors, preachers, and teachers who lived in your neighborhood, and you weren’t isolated in the way that these neighborhoods have become, where these people have left. A lot of people don’t see hope. That leaves another gaping chasm. My example is Louis Armstrong, who lived in his house in his home community till he passed, although he was an internationally acclaimed guy who could’ve lived anywhere else. I want to stay in Baltimore, with my peeps. I’ve been asked why don’t I go, but I feel like I would be leaving myself. This is where I came from. I try not to fear them because that’s like fearing that part of myself. That blackness of myself that can’t find relief. If I am doing well I know that many of us are not. That’s why I do free classes, and if I can’t, I supply all the supplies. All I am saying to you is that I could leave, but Baltimore needs to keep some of those people here to make it better.”

As I told Joyce, many people from this city leave and never contribute to healing the pain and disparities that they escaped from. I often am conflicted about whether to have bitterness toward these runaways, but at the same time I understand why one would run away from such trauma. I also often see these people when I tour, and it’s interesting to see that in many cities I run into people from Baltimore. One thing is for sure: these people carry the aesthetic or energy from the city and take it with them. As Joyce would say, “I think whatever you are, you take it with you. It has been proven to me wherever I am.”

Joyce J. Scott, Lewd I, 2013, hand-blown Murano glass processes with beads, wire and thread, 14 ½ x 18 x 15 inches [courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery,Baltimore]

Another artist whose work is definitely embedded with Baltimore is Theresa Chromati, a mixed media artist and graduate from Pratt Institute. She is known for her digital illustrations for cover art for musicians and her flyers for parties like Kahlon, a party I curate based in Baltimore. Now she is moving toward work that combines painting, digital and paper collaging, and anything she feels can fit into her vision. I went to meet with her in her studio as she prepped for her debut solo show at Baltimore’s Platform Gallery, titled BBW, also known as “Big Beautiful Women.”

“With my artwork, I like to create these figures that might make you feel good or uncomfortable, and make you think about something. I just want people to feel something in their bodies when they see my work, whether they feel awkward or empowered. I want them to feel some kind of emotion. Especially for black womyn—I hope that they find some kind of connection and happiness when looking at the work. I put a lot of whimsical and humoristic qualities within my work, and interject those qualities in a situation where someone is trying to appropriate your entire life. I want to show with all those things we experience in our day-to-day lives, like people invading your space, you will still be you and still be positive and beautiful. As a black womyn you often find people who want to invade your space. At the end of the day I just want black womyn to find some kind of joy in my artwork.”

Theresa moved away from Baltimore for five years, and came back as soon as she graduated from school. “Moving back to Baltimore, it grounded my thinking and helped me sort out my ideas. And being here helps me be relaxed and helps me think about what I want to do versus other places I’ve lived. Whether … I decide to stay here or leave, I feel like just with the inspiration between all the things I’ve seen growing up, and all the womyn I’ve seen growing up in my life, and even still now and the body language of seeing these womyn getting dressed up and that interaction with another helped shape my work and this body of work … shows where I am now with Baltimore, and that’s a great feeling.”

Theresa Chromati, Between a Braiders Weaving, 2016, collaged works on paper, digital, bandana fabric, glitter, kanekalon hair, 48 x 72 inches [photo: Justin Tsucalas; courtesy of the artist and Platform Gallery, Baltimore]

Theresa Chromati, Beneficial Boot Wearer, 2016, collaged works on paper, digital, bandana fabric, glitter conte crayon, 48 x 72 inches [photo: Justin Tsucalas; courtesy of the artist and Platform Gallery, Baltimore]

A lot of creatives from my city often go back and forth, from living away to coming back. For me, I had my time in New York City, but I couldn’t take the environment there. I found it extremely hard to create. Like most people who are transplants in New York, you would spend at least three to five years building a foundation for your career, and that foundation could just be work to find economic sustainability, and not even a real foundation to create work. Theresa Chromati thought the same. “In Baltimore you have that thinking space,” she says. “When I was in New York, I couldn’t think and wasn’t inspired by anything. In Baltimore I like catching the bus and hearing the conversations that people have, and I notice little details, like how people sit on buses, how they cross their legs and stuff—things I could never notice in New York. I’m glad I came back home because I started to love the things that I once hated. Moving forward, I realized that all things are within me now, and no matter where I go, I will take them with me. But Baltimore will always be a place I come back to and just revisit the things that made me. It’s healthy and really important to keep coming back.”

It’s nice to be home and create, but then after while you find yourself back in the same space, resenting your home because you are challenged daily with the oppressive systems that attack black creatives. Says Theresa: “In Baltimore there need to be more platforms that support black artists, and more platforms that inspire black people to feel like they can even make art—which don’t really exist. In a city where there’s so many abandoned properties, yet there are so many loopholes around getting a space. I don’t quite understand it, and it’s very frustrating. I don’t see barely any young black people who have a gallery or even a creative space. Growing up, the only reason … I felt like I could do art was because of the support of my family. It wasn’t through anything else, really. Then, going to the Baltimore School for the Arts, I was provided a safe place to create—but that’s one art school in this city for young kids. [There are] not that many options for young kids to do artwork here or be supported at all. It needs to be known to kids that they can become working artists and make a living out of their art. I’ve been teaching kids, and hopefully I’ve helped them realize that it’s possible.”

Theresa Chromati, Blessed Bonding Woes, 2016, collaged works on paper, digital, bandana fabric, glitter, 23 x 35 inches [photo: Justin Tsucalas ; courtesy of the artist and Platform Gallery, Baltimore]

What does it come down to for the state of black art in Baltimore? It seems now we have people who are protesting the long shade against the growth of black creativity in the city, by either creating their own platforms and sharing them with fellow black folk, or coming back to the city after collecting knowledge and inspiration elsewhere. All I know is that I feel invested in my nesting place, to give back and create opportunities for the kids who are like me, thirsty to shine and express themselves. As Theresa says, “As an artist from Baltimore, you definitely feel a lot of pressure from being from here, because you know what you went through and what other people went through, and you can’t blame anyone for wanting to leave. But I think it’s important to give back to your community, even if it scares you. Whether you want to move back or not. I think it scares people to revisit something that hurts them a lot. But your home is what made you sparkle.” As Theresa’s work creates visions of reality where black women can shine, we must do the same IRL, here at home in Baltimore. I believe it to be possible. But we must also be real: the city of Baltimore needs to help heal the wounds of black trauma that it has inflicted on its people, and I know for sure that allowing black creativity to flourish is a part of that procedure.