Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design

Undeniably, Africa is a diverse and vibrant continent, creating art, fashion, architecture, and designs unique to an African experience that can resonate globally; despite this fact, the continent often gets overlooked, treated as a blank spot on the map. Filling in such perceived “blank” spots is the mission of the Map Kibera trust, whose Map Kibera is one of the projects visitors encounter in Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design. Kibera is an urban settlement with a population of about 200,000 people located just three miles from central Nairobi, Kenya, and until 2009 it was omitted from any urban plan as though empty. Using open-source software, community volunteers began to map Kibera, formalizing their own existence, empowering them to advocate on behalf of its residents. Making Africa, though not organized by an African curator or African institution, is a part of mapping design on the continent.

Making Africa is curated by Amelie Klein at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany, in conjunction with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain. The exhibition made its American debut at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta [October 14, 2017–January 7, 2018], and it is currently on view at the Albuquerque Museum—its second of three planned stops in the US. Organized into four parts, the exhibition begins with “Prologue,” which seeks to explain the size and diversity of the continent through a series of musings by notable thinkers, curators, and artists about the idea of Africa, considering how it is perceived, and what it means to be African. Subsequent galleries divide the work into the sections “I and We,” which asks how design can express identity; “Space and Object,” considering the urban and rural environments created by humans; and “Origin and Future,” exploring the collision between past and present in Africa. Included are the superstars of African contemporary art: Yinka Shonibare, MBE (British-Nigerian multi-media artist), El Anatsui (Ghanaian sculptor), Omar Victor Diop (Senegalese photographer), and Cyrus Kabiru (Kenyan sculptor). In addition to physical objects of art and design, new media projects were highlighted throughout the galleries. They included advertisements, presentations of crowd-sourced data, and documentations of TED Talks and interviews addressing the reclamation of Africa’s future.

The exhibition was particularly memorable in its blurring of design and fine art. South African designer Leanie van der Vyver’s Scary Beautiful (2012) is an architectural pair of shoes covered in chartreuse leather; at almost three feet in height, the heels should logically elevate the model to tower above everyone else. As seen in the accompanying video, however, the construction forces the model into a hunched over position, making each step taxing—a harsh and troubling human contrast to the long technological elegance of these engineered heels.

Duro Olowu, Look 12, 2013-2014, from Birds of Paradise Autumn/Winter 2013/2014 collection, cape: embroidered silk; pants: silk and viscose; top: viscose, georgette, and silk [© photo: Luis Monteiro; courtesy of the artist and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta]

Equally beautiful and disorienting is Skhayascraper (2013) by South African designer Justin Plunkett. This skyscraper composed of shanties stands solid and tall, yet the fundamental instability of shacks, here stacked vertically, makes just looking at the collage feel as though you will topple over.

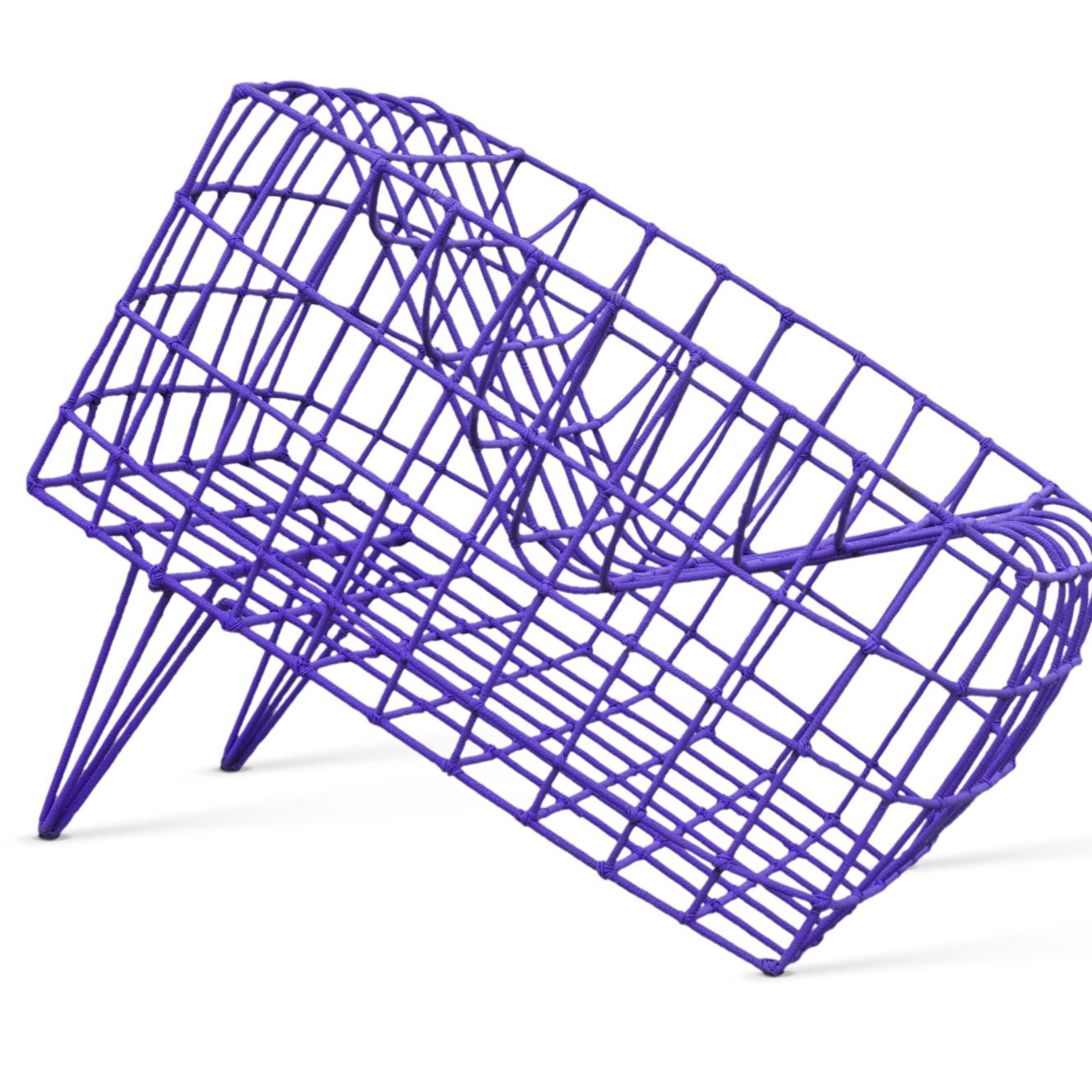

Two series by Belgian-Beninese photographer Fabrice Monteiro are featured in Making Africa. One, The Prophecy (2013), was created in collaboration with fashion designer Doulsy (Jah Gal, from Senegal). These photographs are incredible examinations of formerly pristine environments that depict, for instance, an oily but elegant monster emerging from Dakar’s Hann Bay, a body of water polluted by run-off from an adjacent slaughterhouse. In another image, a woman wears a owing ball gown of trash atop a burning mountain of garbage accumulated on what was once a green marsh. Her printed cloth-covered dreadlocks reach out into the polluted atmosphere as she dangles a mangled doll above the burning heap. Monteiro’s The Missing Link series was also the result of a partnership with a fashion brand—in that case with Bull Doff, a label established by Senegalese designers Laure Tarot and Baay Sooley. In a work called Joe (2014), renowned performance artist Issa Samb, who died last spring, sits clad in neo-gothic black and enthroned on a rubber tire chair, yet flanked by a staff and umbrella that speak to a generalized traditional culture. Samb’s throne resonates with Senegalese artist Amadou Fatoumata Ba’s Canapé Tressé and Pouf Tressé (2014)—a bench and an ottoman woven out of worn rubber tires displayed in an adjoining gallery. Set in a broken-down landscape, the designs seem distinctly built up with the dystopian flavor of Mad Max: Fury Road.

Making Africa denies being a continental exhibition that seeks to represent a comprehensive survey of design in Africa. However, the size and scope of the exhibition falls in line with a long list of contemporary African exhibitions dat- ing back to the early 1990s—including Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art (1992) and The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (2002), both held in New York; and Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent, held in London in 2005. These exhibitions were criticized, often not for what was included, but for what was left out. In the case of Making Africa, there is so much content that no one could reasonably expect to cover it in a typical museum visit, but it is also clear that it has only scratched the surface of the wealth of African design. The more one experienced of the exhibition, the more the exhibition’s apologetic “Prologue” emphasizing the size and diversity of the continent seemed unnecessary—Africa’s vastness and vision are clear. Making Africa is expected to travel to seven museums before it retires. At this point, however, is not expected to travel to Africa.