Michael Rakowitz:

A Desert Home Companion

Rakowitz, Dar Ah Suhl 18, 2014 [photo: RCH | EKH art documentation; courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery]

How to describe an artwork that has yet to be made or has yet to happen? It's a proposition made more perilous by the complexity of the work itself and, when it comes to artist Michael Rakowitz, complexity is always a factor.

Share:

Rakowitz’s works are charged by logistical nightmares, which create an uncertainty that pervades them from their conception, to their hopeful conclusion. His attempt, for a project called Return (2004-ongoing), to revive his grandfather’s import-export business by shipping a literal ton of dates from Iraq resulted in three weeks of delays and multiple failed attempts to cross international borders. The dates rotted in transit and never made it to their final destination—a storefront in Brooklyn. Rakowitz learned from the refugees coming in and out of his Atlantic Avenue store that the disrupted path of the dates mimicked many of these individuals’ own initial attempts to escape their countries of origin; in this way, the unforeseen tangles of this project were more revealing than the work might have been if it had gone as planned. So, when Rakowitz announced his plans to host a 75-minute live event at Independence Mall in Philadelphia intended for summer 2016, featuring live performances by Iraqi musicians and war veterans, traditional Iraqi cuisine and vendors of Iraqi cultural goods and items, and a parade of Arabian horses—refugees in their own right, according to Rakowitz—audiences could be assured that even (or especially) if things don’t go exactly as planned, the result will be more valenced and intriguing for all its unforeseen incidentals. And there have been plenty of unforeseen incidentals.

Sponsored by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, this event was proposed as a collaboration with the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, and with Warrior Writers, which offers writing and arts workshops to military veterans, service members, and their families. Warrior Writers’ overall intention is to focus on the launch of a 10-episode radio program, which will be distributed to stations around the United States through Prometheus Radio Project, as well as through partners in Jordan and podcasts on the Internet. Each 30-minute episode will feature stories from American veterans of the Iraq War and members of the Iraqi diaspora in America. These in-studio recordings will be layered with field recordings from Iraq, music, descriptions of Iraqi cultural traditions, and found sound to create passages that will accompany the live performance planned for Independence Mall.

The project’s title, A Desert Home Companion, is a wry riff on A Prairie Home Companion—a live variety show broadcast on National Public Radio, where, until July 2016, it was hosted by the incorrigible and polarizing Garrison Keillor. Prairie, for many, is a groan-inducing platform for personal stories, folk music, and notoriously corny Midwestern-centric jokes. When I asked Rakowitz about Keillor’s influence on his project earlier this year, Desert Home Companion was only a working title, though it seems to have stuck. “I’m not going to say it’s a terrible title,” Rakowitz said, laughing. “The prairie becoming a desert can be simple and intriguing and humorous ….”

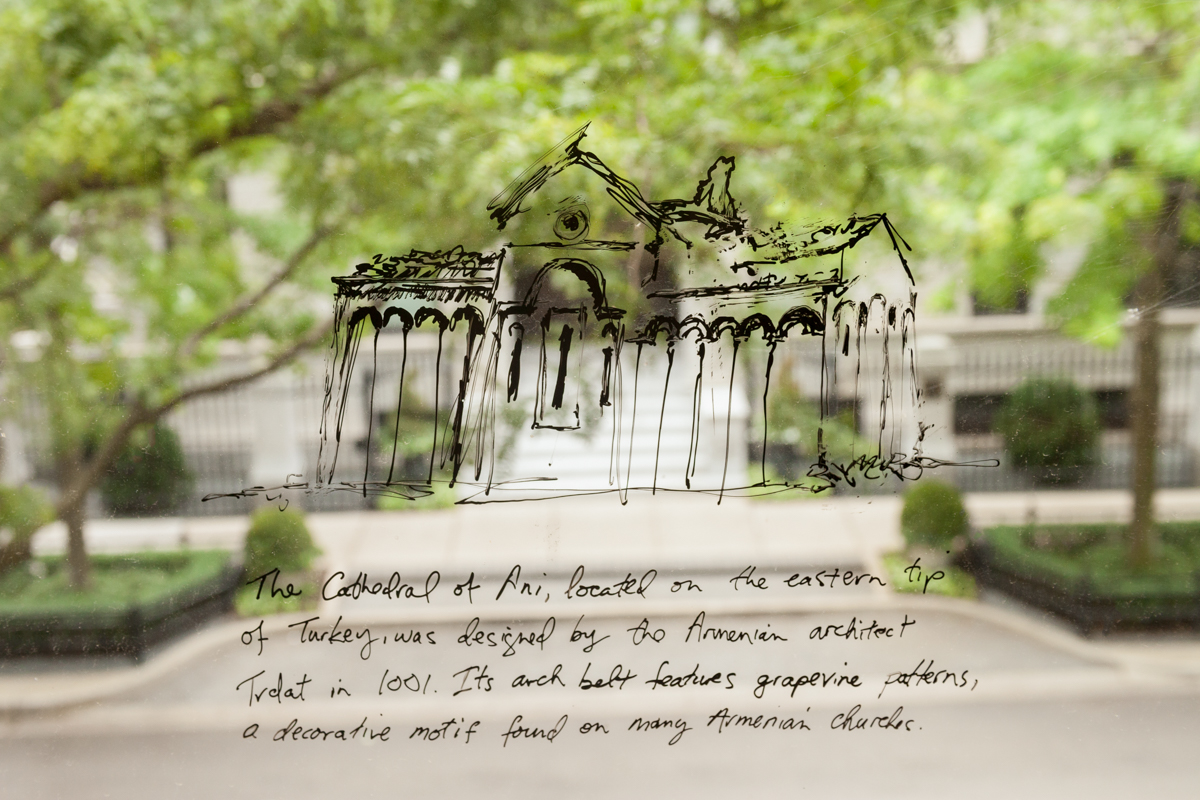

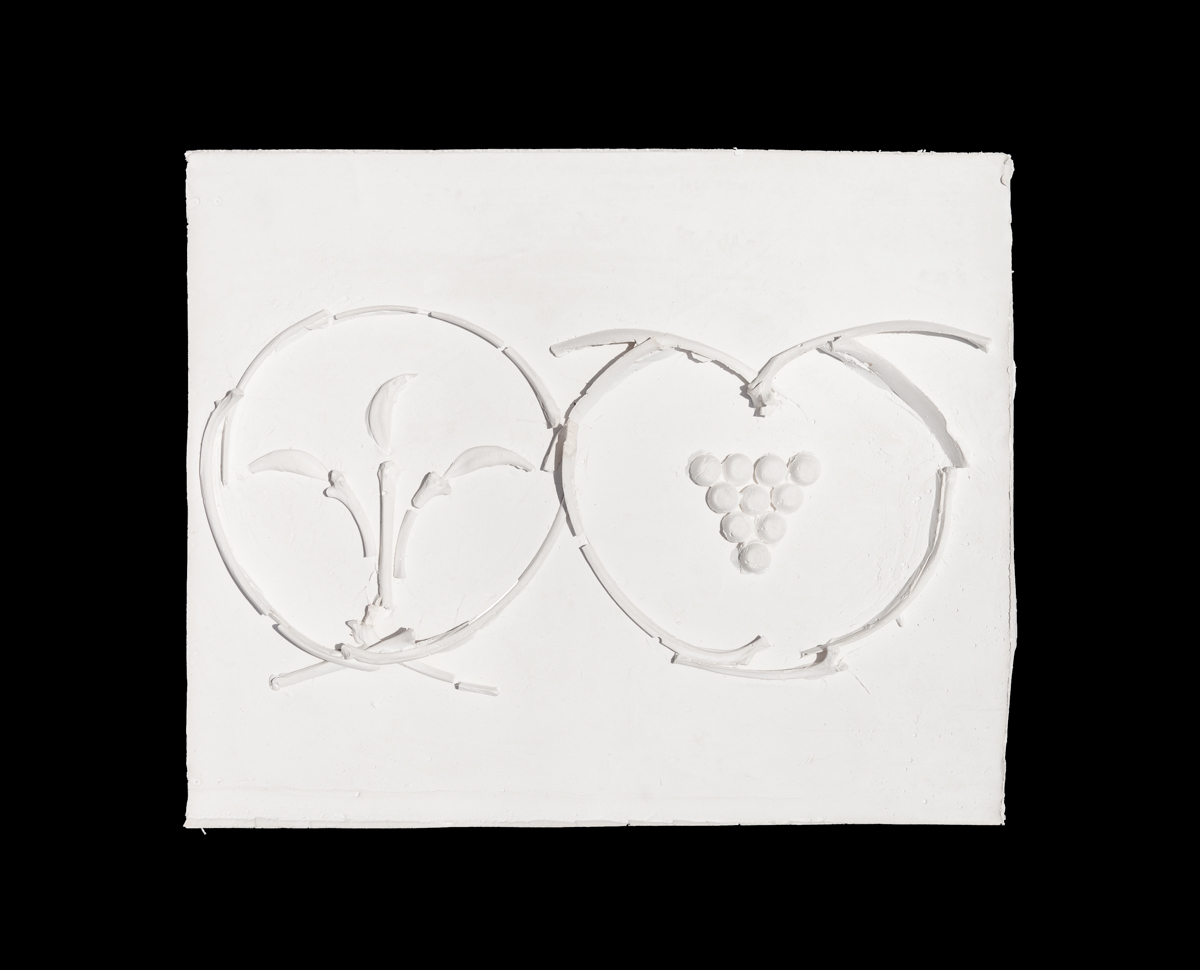

Michael Rakowitz, Dar Al Sulh (Domain of Conciliation), 2013 [courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery]

Michael Rakowitz, Dar Al Sulh (Domain of Conciliation), 2013 [courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery]

The genesis of Desert Home Companion came out of conversations with independent curator Elizabeth Thomas, who met Rakowitz while working with the Berkeley Museum of Art’s MATRIX Program for Contemporary Art in 2007. From the start, they focused on Philadelphia, in part because of Thomas’ work with the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, but also because of Rakowitz’s fascination with the city as emblematic of America. “Growing up in New York, [for me] Philadelphia was by extension part of my life. It was driving distance, and my parents took me often,” he told me. “I became interested in the idea of it being ‘ground zero’ for America, as part of the historical mythology of the country.” When Rakowitz was a young art student, the Rodin Museum seemed to be “one of the most beautiful places in the United States”; so, when Thomas invited him to visit the city, he remembers, one of the first things he did was research Philadelphia “as a site where new immigrants pledge allegiance,” and the “meaningful space” of its Independence Mall and the Liberty Bell.

Radio seeped into the project and became its primary medium after conversations with Iraqi immigrants in Philadelphia, in particular with Bahjat Abdulwahed—who has been described as the “Walter Cronkite of Baghdad”—and his wife Hayfaa Ibrahem Abdulqader; both were prolific journalists in Bagdad before immigrating to Philadelphia in the late 2000s via Amman, Jordan. As contributors to Desert Home Companion, Abdulwahed and Abdulqader have been researching the sounds of Iraq, as well as training other participants in proper Arabic pronunciation. Other Philadelphia refugees have suggested recording the sounds of cooking, or asked if they can do shout-outs to friends still in Iraq, all of which Rakowitz is enthusiastic about (“I thought it was fucking brilliant,” he said). They’ve also found recordings of Abdulwahed giving radio reports in Iraq in the 1950s, as well as recordings of refugees in Amman, which according to Rakowitz is like a Little Baghdad due to the number of Iraqi refugees who have ended up there. “The language, the songs, and the spices remain [the same],” he said. “The only thing that’s different is the weather.”

Rakowitz has been studying radio as a medium for some time. He has been listening to Serial and The Moth, among a slew of other popular podcasts, in addition to archival propaganda radio from the Vietnam War and North Korea, and to fan podcasts about science fiction and comic books. “I’m trying to figure out what works, what holds my attention, and what doesn’t,” he said. Rakowitz has strong childhood memories of listening to the radio, as well, which include the sounds of classic Americana, and those of diaspora communities. Growing up in Great Neck, NY, he listened to baseball games (he’s still a Yankees fan) and music; he also became interested in shortwave radio and the clashes of propaganda it presented. “I’d listen at night, when the signal was stronger,” he recalled. “You could hear Iraqi radio and Voice of America, and there were these call signals they’d play for 15 minutes before the broadcast started to let people across the world know their dial was tuned to the right station. The call sounded like the beginning of an anthem.”

Bahar Yurukoglu, Halo, 2015, pigment print

“I became interested in the idea of it being ‘ground zero’ for America, as part of the historical mythology of the country.”

-Michael Rakowitz

Rakowitz remembers that Hezbollah radio would sometimes break through to interrupt the broadcast. “Syrians used to jam the Israeli broadcast by [broadcasting the sound of] someone pouring water from one glass into another, which became this layer [of sound] over the radio program. The history of pirate radio, and all these clandestine broadcasts I was able to pick up on shortwave radio [as a child], is incredibly interesting to me, [particularly] how you circumvent, and interrupt [these channels].” These memories easily register as the seed of the current project—a memory-driven trail that is common when talking to Rakowitz about his work, and is as much testament to his impressive mnemonic faculties as it is to the depth of his engagement with intersecting personal and shared histories.

Growing up, Rakowitz was very close to his now-deceased grandparents, who themselves were refugees from Iraq; their stories from the country were a consistent source of fascination and served as the backdrop for the traditional Iraqi meals his mother would prepare. This seemingly mundane backstory becomes vital in hindsight. In the years after 9/11, aghast at the misinformation surrounding those events and the skewed depictions of Iraqi life and culture flooding the media, Rakowitz asked his mother to share her traditional recipes. They became the foundation of Enemy Kitchen (2006-ongoing), a series of food-based artworks that has evolved over time. The first iteration was a series of after-school cooking classes at the Hudson Guild community center in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. Many of the students had family stationed in Iraq at the time, and the classes quickly became a fertile opportunity for debate. In 2006 Rakowitz moved to Chicago for a position at Northwestern University, and Enemy Kitchen’s classes morphed into a food truck specializing in Iraqi cuisine; the vehicle would park in neighborhoods all over Chicago, including locations near military academies. The truck eventually became popular with the Obama campaign when it was headquartered in Chicago’s Prudential Building. The featured dish was masgouf, a dish of seasoned, grilled carp, and the national dish of Iraq.

In 2014 the idea evolved again. For a work called Every Weapon Is a Tool If You Hold It Right (2014), Rakowitz collaborated with Iraqi émigrés and US veterans to make masgouf with carp fished from Chicago’s waterways. Carp is an invasive species in Lake Michigan and the Chicago River—a kind of ecological immigrant, in Rakowitz’s view. The skewers used in preparation for cooking the fish were made from Iraqi and American bayonets; the grills used to cook the fish were made with recycled metal from Humvees used in Iraq—gestures that put the project’s title into action. For the Independence Park celebration, many of those elements—the bayonets and Humvee grills—are likely to reemerge, again in the preparation of masgouf. The added twist proposed is that the cooking fire will come from the flame of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, transported by torch, Olympics-style. “It’s idiosyncratic sourcing that has been prevalent in the work before,” Rakowitz noted.

In every piece of Rakowitz’s work, the idiosyncratic creates layers of complications, some of them jaw-dropping or even repulsive. For a work called Spoils (2011), a Creative Time commission, Rakowitz designed a dish for Park Avenue, a high-end Manhattan restaurant. It featured elements of an Iraqi dessert made with date syrup and tahini, but paired with American venison, for contrast—a veritable diplomatic standoff, tastefully resolved on the plate. The serving dishes themselves, however, were perhaps less palatable than the meal: the plates came from Saddam Hussein’s personal collection, pieces of which Rakowitz had acquired on eBay—”war trophies” purchased from American soldiers, and Iraqi refugees. Many diners opted out of ordering the dish, though some who did remarked on the similarity between Hussein’s Wedgewood china and their own.

Michael Rakowitz, The Flesh Is Yours, The Bones Are Ours, 2016 [courtesy of the artist and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts]

If the presentation wasn’t enough to intrigue, the timeliness of the Spoils project was critically thought-provoking: only two days before the dish was supposed to come off the menu, Park Avenue received a cease-and-desist letter from the State Department. The war in Iraq was officially ending, it read, and the United States government intended to seize the plates and return them to Iraq, in the care of Prime Minister Nouri al-Malaki. Rakowitz was of course happy to oblige, and filmed the proceedings. He was told that the plates would eventually become part of an exhibition on Saddam’s life, in a museum housed in one of his former palaces. The display will also mention Spoils, thus forever affixing Rakowitz’s artwork to the complicated material existence of a dictator. Spoils became a part of the media’s take on national events that week as well—both The New York Times and The Rachel Maddow Show prominently mentioned the project in relation to the withdrawal of the US-led coalition from Iraq, and thus the projected end of the Iraq War. Here again, the idiosyncratic aspects of Rakowitz’s work were very quick to become its most fruitful aspects.

Yet beyond the events that lead to front-page news, there are the subtler connections and surprises that, in Rakowitz’s mind, equally energize and give meaning to the work. Rakowitz speaks passionately about the connections made, via Enemy Kitchen, between Chicago-area war veterans and Iraqi immigrants—many of whom realized they’d previously intersected in Iraq.

In many ways, such conversations feel as though they could only be products of these types of creative efforts. Rakowitz’s work has been featured in documenta and the Istanbul Biennial, and at the Tate Modern, to name a few institutional contexts, but he is more likely to celebrate the work of his collaborators than he is to discuss his own résumé. Many of these collaborators have an ongoing, long-term relationship to Rakowitz’s work. For the live events in Philadelphia he has proposed to feature war veteran/artist/professional performer Aaron Hughes, who has worked with Rakowitz on past projects in Chicago. At the project’s center are Bahjat Abdulwahed and Hayfaa Ibrahem Abdulqader—as Rakowitz says, “the project is being built around them.”

Rakowitz also says that Abdulwahed’s life is intertwined with Iraqi broadcasting in ways that are both personally and historically significant. Abdulwahed and Abdulqader met while they were both working for Iraqi television (their daughter, incidentally, became a broadcaster in Jordan). There, Abdulwahed reported on some of the most critical moments in 20th-century Iraqi history: he covered the assassinations of Prince ‘Abd al-llah and Prime Minister Nuri al-Said amid the events of the 1958 Iraqi coup d’état, as well as the subsequent Ramadan Revolution of 1963. Abdulwahed was on air during the Iran-Iraq War and the first Gulf War; he was also the play-by-play announcer in the infamous 1971 fight between Iraqi professional wrestler Adnan Al-Kaissie—also known as General Adnan—and André the Giant in Baghdad.

Rakowitz, Dar Ah Suhl 10, 2014 [photo: RCH | EKH art documentation; courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery]

Rakowitz had used Abdulwahed’s wrestling commentary as part of his exhibition The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own, which took place at the Tate Modern in 2010; Rakowitz still finds it astonishing that the two of them eventually intersected. “We met in 2014,” he said, “and Bahjat and Hayfaa have become like adoptive grandparents.” Abdulwahed and his wife, in turn, became very excited about the Desert Home Companion project in their adoptive hometown. In light of Abdulwahed’s experience, Rakowitz recalled, “I thought the best thing to do was reactivate Bahjat’s background.” The story is one that Rakowitz is passionate about, and he sees it as representative of so many immigrant experiences in America. “The previous work and accomplishments of immigrants to America never translate: guys with medical degrees end up driving taxis, which is one of the most brutal aspects of immigration to this country. The goal became to give Bahjat his show back.”

Rakowitz’s initial aim was to re-create Abdulwahed’s former newsroom as the set and main stage for the Independence Mall performance; while developing this idea, he began thinking more about radio’s limitations and strengths as a medium: “I became energized about the idea that the radio program can be a place where things that can’t be seen can be said. It allowed me to think about ways to bring in the veterans’ community, to hire them and mobilize some of the stories they’ve written down as part of Warrior Writers initiatives … part of the narrative therapy where the landscapes of the US and Iraq collapse on each other and become these hallucinatory descriptions.” On adapting these varied visual and verbal efforts for broadcast, Rakowitz noted, “The great thing about radio is that you’re not overburdened with the visual: it allows you to use your own imagination.”

Rakowitz is interested in the in-process project’s ability to reconstruct Iraq—”not as a replacement,” he said, “but as a surrogate or placeholder.” For him, it’s about capturing voices, and “Bahjat’s voice is incredible,” he said. “It’s the most caramel voice I’ve heard in my life. I’m interested in his voice existing like a Proustian callback to something people might recognize, or how people’s testimonies can cause others to recollect their own stories, and how this can reanimate something about Iraq that’s been dormant.” There are aspects of return for Rakowitz personally, as well. As of this spring, his hopes were to make contact with the now-retired wrestler Adnan Al-Kaissie, and to get him together with Abdulwahed either to reenact the play-by-play of the match with André the Giant or to talk about what it was like. In the latter scenario, Rakowitz would, following his research for the Tate Modern piece, involve himself: “We’ll be three Iraqis talking about the 1970s in Iraq,” as he put it.

In the months prior to its summer debut, however, the Philadelphia project was inevitably being shaped and changed by circumstances outside of Rakowitz’s control. When we discussed the work in early 2016, Rakowitz mentioned Abdulwahed and Abdulqader’s commitment—”They’re very insistent that if they’re going to do this, they’re doing it right”—but also expressed concern over Abdulwahed’s health issues. By the time of our follow-up conversations, Abdulwahed had taken a turn for the worse, and he was in intensive care. His health at press time was still tenuous. As such, it has been a trying time for Rakowitz, and for Abdulwahed’s community. How this will affect the project, which is currently on hold until summer 2017, is uncertain; true to Rakowitz form, however, he insists it will assuredly happen, in some form, at some stage. As Rakowitz said, speaking of himself and the others involved in this project: “It isn’t about nostalgia; it’s more like this is what we’ve been trained to do. America needs to know about the Iraq that’s disappeared, and Iraqis need to remember it.”

The Flesh Is Yours, The Bones Are Ours, installation view, May 19 – August 13, 2016, [photo: RCH|EKH art documentation; courtesy of Michael Rakowitz and Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts OR Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago]

Lilly Lampe is a writer and designer based in Brooklyn, NY.