Milo van der Maaden:

the unutterable thing

"Other forces are surely at play in defining and limiting what gender is, but what is certain is that the current 'universal' and 'natural' ideas of gender now stem in part from colonialism and a need to centralize and control non-western forms of life." —Nila Nokizaru, "Against Gender, Against Society," LIES Volume II, 2015

Share:

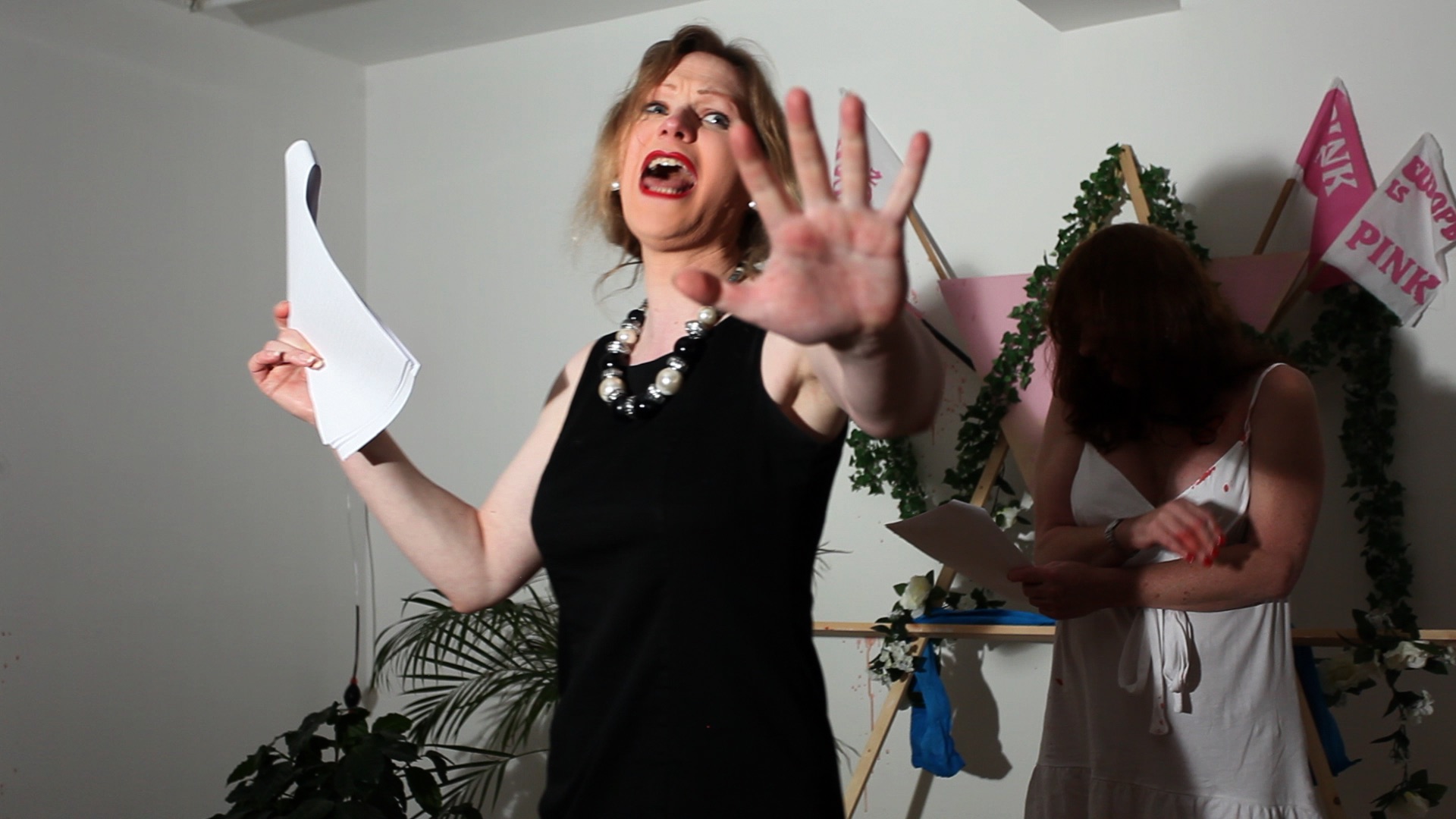

The mood was carnivalesque at Milo van der Maaden’s the unutterable thing (January 29–February 6, 2016). A handful of leafy plants evoked a tropical setting domesticated within London’s Rowing gallery, temporarily transformed into a theater. Grotesque masks—one painted red, another white, and another blue—hung from nails on the walls, and sat at the base an altar-like structure installed centrally at the back of the stage. Sculptural objects sat like props, ready to be activated; some of them, like the masks, were rigged to be able to issue fake blood. A potted cactus was ripped open to reveal a candle at its core, and matches studded its surface. It seemed to have come into the world through an act of violence, yet, with its placement and design, resembled the kind of ritual mourning object left at a gravesite or a memorial. Four pink-and-white flags adorned the stage, printed with proud declarations: two of them read, “EUROPE IS PINK”; the other pair claimed, “PINK IS NATION.” Europe would be the LGBT-friendly set on which the unutterable thing, van der Maaden’s theatrical adaptation of Louis Couperus’ 1900 novel The Hidden Force (translated from the Dutch language original De Stille), would play out, interpreted by four actors—Tina King, Victoria Gigante, Victoria Elizabeth, and Hugo Trebels—from the London queer community.

There is an at times uncomfortable overlap between the social politics of Europe, the United States, and Israel, which have, despite anti-immigration efforts and Islamophobia, been relatively supportive of their LGBT communities. Since 1960 large numbers of Muslims have emigrated from Turkey, Morocco, Surinam, and Indonesia to the Netherlands. Meanwhile, in recent years, right wing politicians have enjoyed new popularity among Dutch voters: according to a February 2016 article in The Guardian, Geert Wilders—who, like Donald Trump, wants Muslim immigration stopped to prevent an “Islamic invasion”—is on course to come out on top in a general election.

Milo van der Maaden, the unutterable thing, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) packages its support of LGBT rights with a pronounced distrust of Muslim immigrants, and blames Islam for instances of homophobia and anti-Semitism. (This is the political and commercial phenomenon of “pinkwashing”—”There is no pink door leading to a secret pathway through the Wall for me,” as Palestinian Queers for Boycott/Divestment/Sanctions (PQBDS) activist Sami Shamali has said.) In the UK, where van der Maaden is based, the LGBT group officially affiliated with the xenophobic and anti-Islamic UK Independence Party (UKIP) controversially joined the 2015 London Pride parade.

With LGBT rights having been won through progressive politics, how could supporters of a party with racist and isolationist agendas be tolerated, regardless of their support for queer rights? the unutterable thing is one of a number of theatrical works to have sought to address this question. Critic Matthew McLean has suggested that a recent proliferation of artists’ plays could be due to theater being more adept than performance art at responding to an artist’s desire “not to explore, question, blur, tease, engage, activate or reflect upon, but simply to speak, make a point.” (“A play lets you say everything,” explained one artist interviewed by McLean.) Yet what the unutterable thing deals with is the parts of conversations surrounding free speech, or its oppression, that somehow elude expression. Van der Maaden approaches this in part by focusing on the mouth itself, which is sometimes defiled with blood or cactus thorns. When, at Rowing, one character threatened to bite the tongue of another, the chorus cried out, “Wash your mouth, wash your sins away!”

Milo van der Maaden, the unutterable thing, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

The Hidden Force has long been viewed as the first critical account of Dutch colonialism, and it used fiction to detail the ways that Western rationalism and European values were misapplied to what is now Java, Indonesia—the Dutch East Indies from 1816 to 1942. The novel has been repeatedly adapted for Dutch TV and radio since the 1970s; in 1994 The New York Review of Books called it “one of the masterpieces to come from the colonial experience”; and in 2010 Dutch director Paul Verhoeven (of Basic Instinct, Showgirls, and Starship Troopers) was reported to be making it into a feature film. In Couperus’ foreword to Raden Adjeng Kartini’s Letters of a Javanese Princess (1921), Couperus wrote of Indonesia: “I felt that while we Netherlanders might rule and exploit the country, we should never be able to penetrate its mystery. It seemed to me that it would always be covered by a thick veil, which guarded its Eastern soul from the strange eyes of the Western conqueror. There was a quiet strength, ‘een stille kracht’ unperceived by our cold, business-like gaze.” In van der Maaden’s critical adaptation, Couperus’ florid and orientalizing language is repurposed in an attempt to measure the extent to which the ideological frameworks, vocabularies, and behaviors of the colonial past have been dismantled—and to pantomime their persistence into the present.

This work stages an intervention in the under interrogated racist atmosphere of The Hidden Force, and revives and reclaims what it does and does not say. It is not without a taste for humor or for the surreal, however. Couperus describes an Arab quarter of Java as radiating “unutterable mystery like an atmosphere of Islam that had poured forth the dusk, fatal melancholy of resignation;” in the unutterable thing, this passage is accompanied by some additions: “When the carriage drove into the Arab quarter … this quarter seemed to radiate its unutterable mystery like an atmosphere of Islam that spread over the whole town, as though it were Islam … Islam … Islam … Islam … Islam … Islam … Islam … that had poured forth the dusky, fatal melancholy of resignation, which filled the shuddering, noiseless evening … Couperus wrote quite distastefully.” This is an indulgence, a provocation of the decadence of the original writing, which ironically responds to the “unsayable” with more, not fewer, descriptors. As a result the unutterable thing is a kind of contemporary burlesque, complete with a chorus chanting such phrases as “We are all Europe”—a nod to the “Je suis Charlie” campaign and similar collective expressions of solidarity with specifically non-Muslim victims. At Rowing, “We are all Europe” hung in the air once it had been spoken, leaving the audience with an echoing sense of such collective inclusiveness, and of the queer community’s particular status in the performance of anticolonial projects.