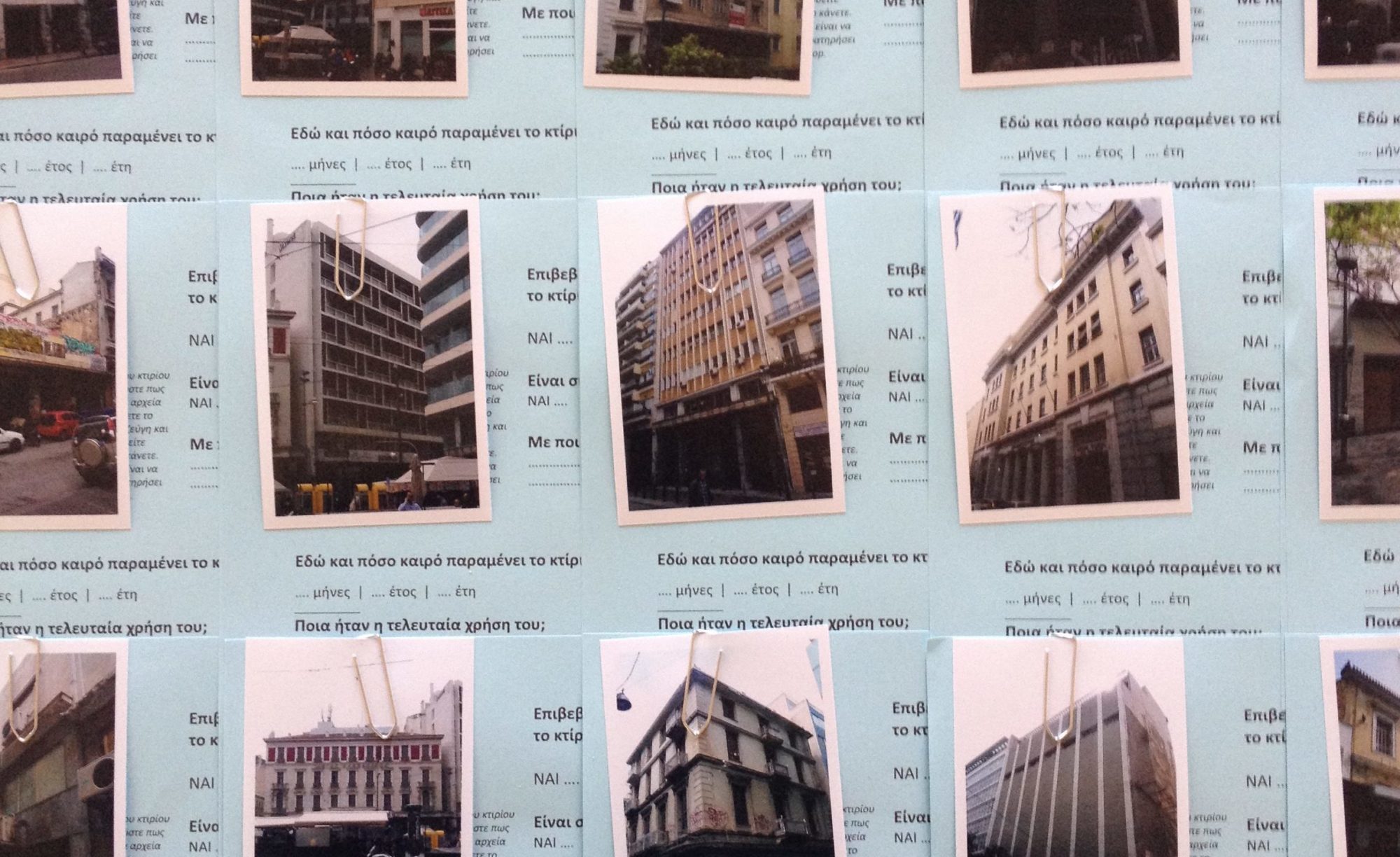

Fanis Kafantaris, Speleo, installation view. Bageion, Athens Biennale OMONOIA

The School of Athens

Share:

The dominant global art discourse is currently boosting two prevailing stereotypical images of Athens today. In one view, the city is a frozen one where ancient ruins meet the ruins of neoliberalism, its neighborhoods turned into barren “steppes,” as Paul B. Preciado, curator of public programs for documenta 14, wrote in the French newspaper Libération, describing homes where residents wear coats indoors and share the hearth with a special kind of Greek cockroach.1 In the other view, the same Athens has become a “workshop” of creative energy in the wake of its debt crisis, a place where the art scene is attractive as an incubator of freedom and survival strategies.2 Foreign curators have often celebrated the creativity coming out of Athens in recent years, not only as an affordable and romantic place of art production but also as a hub for do-it-yourself funding models and sustainable art activity. While the left-wing Syriza party’s “youthful” government claims to represent a paradigm shift for Europe, Athens is outlined as a place of resistance, education, and strategic solutions for resiliency—that is, a place to learn how to have an art scene without having any money, through alternative economies and communitarian practices.3

This image is problematic, particularly when viewed through the lens of European precarity, mitigated by privatization and cuts in funding for cultural programs and the humanities. Such a positive spin puts the emphasis on the emergent characteristics of Athens’ art scene—such as flexibility, sustainability, resourcefulness, the creation of informal networks, and social practice—and connects it to the contemporary interests of local and international arts institutions. Can we resist the exotic view of Athens as a southern experiment in creative sustainability during times of crisis?

Back in the post-Olympics Athens of the mid Oughts, many artists, curators, galleries and institutions of my generation put a lot of energy into establishing a dialogue with the “global” (though mostly Western) art world; we shared many heated discussions on the terms of the much—desirable inclusion of the “new Greek art scene” on the “global art map.” Given that recent history, the exoticizing narrative of creative Athens today feels like a joke.4 The city suffers from a lack of a strong sociopolitical conscience and weakness in critical and theoretical writing; meanwhile, the state is completely indifferent to art and to cultural programming and education, and art impresarios are so focused on the exportation of the city’s supposed “scene” abroad that they undermine the creation of a discourse about its identity, its evolution, and its real institutional needs. Although peripheral, Greece’s art scene wasn’t quite exotic enough to be as attractive as other peripheral scenes of the 1990s and early 2000s; its relationship to and role within the peripheries and centers of the global art world were never quite claimed.

National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, Greece [photo: Despina Zefkili]

The discourse surrounding the nature of Greek contemporary art changed since 2007 and the first Athens Biennale—which was called “Destroy Athens.” Consider Omonoia, the 2015-2017 iteration whose name means “concord.” It must be all that new artistic “energy”: today the Biennale struggles to find funds to survive (its first edition was sponsored by Deutsche Bank). The National Museum of Contemporary Art, which played an important role in establishing alternatives to the status quo maintained by Greece’s commercial galleries and private institutions, has yet to return to its permanent location, an old brewery it occupied from its opening in 2000 until renovations began in 2003, thanks to stalls in funding for the move. Private institutions, such as collector Dimitris Daskalopoulos’ NEON, now support the majority of Athens’ “independent” large-scale exhibitions; local galleries are fewer and less influential than they were in the early 2000s. Yet artist-run project spaces, almost non-existent 12 years ago, are very active throughout the city, which has led to a kind of new institutionalism. Arts-critical writing originating in Athens is almost non-existent.5 What little criticism there is tends to focus on secondary discourses surrounding institutional politics, rather than on the art produced and exhibited. A new interest in talks and lectures is nonetheless palpable, perhaps motivated by funding for educational programming by different art institutions.The presence of documenta in the city—the exhibition opens in 2017 in both Kassel and Athens—has put pressure on the local community, which has to define itself with respect to the othering gaze of northern European curators coming to “learn from Athens.”

As curator and critic Evangelia Ledaki has argued, when the proliferation of artistic practices and political emancipation are cut off from each other, and do not grow together, we are left with a creative acceleration process that lacks self-reflection and structural criticism. Responding to the supervision of a sovereign Other and following the categorical imperative of creating as dictated from above, the art produced fulfills the global expectations of creative vibrancy while trying to fill the void of meaning that emerges in crisis.6

The current Athens Biennale is actually two in one: initiated in 2015, it will continue though 2017. Its title—and its programmatic strategy—might be seen as a symptom of the local art producers’ having to deal with a lack of funding on one hand, and with the pressures imposed by the outside world’s assumptions about a city that runs on unprecedented creative energy on the other. In an effort to act as a true incubator for art and ideas, the first intervention for Omonoia, called “Synapse 1—Introducing a laboratory for production post-2011,” took place over the course of 11 days in November 2015 and included an international summit devoted to the topic. It also brought together Athens’ artist-run and independent spaces and artist groups in an empty, rundown landmark, the former Bageion Hotel, which was a hub for artists and intellectuals during the interwar period. In previous editions, the Athens Biennale has acted as a catalyst supporting different interdisciplinary voices and giving a boost to the city’s independent energy. This time, though, it seems to adopt the position of an outsider/observer bringing together different artists and spaces, connected primarily by a vague idea of collectivity, and vividly summarizing the energy of the local independent scene without offering the intellectual tools and contexts for decoding it, as one would expect from an institution so closely tied to the evolution of the Athens art landscape.

Addressing the phenomenon of “energy” (as in, “creative”) as an empty signifier, the Temporary Academy of Arts for professional and amateur education (PAT)—part mobile institution, part experimental education art project—organized a series of performative talks called the “Soft Power Lectures” (2015-2016) in conjunction with ACTOPOLIS, an art and activism project with a flair for urban development that has support from Athens’ local Goethe-Institut.7 In their statement, curators Elpida Karaba and Glykeria Stathopoulou ask if it is possible to take advantage of the exoticization of the crisis in order to produce a “beneficial” branding strategy. In that way, they hope for concrete benefits to persons active in the arts and humanities—one way that the project set out to explore how a city and an academy might exercise “soft power” in order to hegemonize discourse surrounding themselves, their constituents, and their environs.

Urban Dig Project, installation view, Bageion, Athens Biennale OMONOIA [photo: Urban Dig Project]

Athens arts institutions aside, the question remains as to how local art practitioners address their own practices. Recently PAT invited artists, curators, and activists for a live collective interview in a café near Athens’ central Omonoia Square. Interestingly, many of the people interviewed argued that they do not understand art as a vocation: though they work full time in the field, for instance, they do not make sufficient money to cover basic daily expenses. Few of the artists present shared the opinion that the local scene should take advantage of its exoticization by others, or that it should attempt make a profit from its potential role as a “model” or case study, as other peripheral scenes have done. However cynical this proposition might sound, it highlights the unregulated nature of contemporary art at large, but particularly in Greece, which has failed to create a consistent or reproducible narrative for this particular brand of contemporary “creativity.” (It is similarly characteristic that the “Greek Weird Wave” in cinema established itself in the global festival circuit but was never adopted or embraced by the state itself.) At a time when there is an unprecedented interest in the contemporary Greek art scene, the Greek ministry of culture launched a new art prize—then awarded it to a 90-year-old, well-established traditional painter.

During a recent talk at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens Chris Dercon, former director of the Tate Modern in London, suggested that the National Museum of Contemporary Art’s failure to reopen doesn’t matter so much, given that the city has the biennial, as well as documenta and NEON—factors that present Athens as a paradigm for the “flexible” museum of the future. Although the congress inaugurating the Athens Biennale touched on the precarity of creative jobs in the city, the ideologies behind such “flexibility”—behind “smart cities” and the like—rely on the exploitation of voluntary work by major institutions. One cannot ignore that the symbolic/cultural capital churned by the Athens Biennale is largely based on the voluntarism of “forever young” local art organizers and practitioners who are grateful simply to have an international platform.8 An institution prized by the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) for rethinking the idea of the biennale—something that seems to be happening only in situations of crisis, as ECF director Katherine Watson has said9—is still unable to ensure funding for its participants. Moreover, South magazine, an Athens-based publication dedicated to a stylized cultural atmosphere of “southernness,” has been “adopted” by documenta; its symbolic capital has been acquired, since its existence, through the voluntary participation of writers.

Such examples of poor political thinking show that the complexities of the local situation are not obvious in the assumption that “crisis” simply produces “creative cities,” and creative subjects. Even the new emphasis on performance, for instance, should be seen in connection to the systems of value governing immaterial art works, and in the context of the requirement of constant presence, both of the artists and their audience. The narratives of contemporary urban centers as “energetic” are largely constructed, traded in a market of symbolic capital that conforms to regulatory urban projects and corporate interests. In that context, ideas like collectivity, performativity, “inventive” institutional models, and alternative commons lose their radical potential and are thus limited to harmless themes incorporated, in Athens’ case, in the austerity measures of neoliberal policies.10 (This is why the question of how we can “institute differently,” as Maria Hlavajova of Former West and basis voor actuele kunst (BAK) put it at the Athens Biennale’s November 2015 inaugural congress, is so critical today.)

Discourse surrounding art in post-1970s Greece has historically focused, for the most part, on an individualistic sphere and formalist analysis, which of course laid the groundwork for a separation of the personal (the artist) from the political sphere. The desire to establish and secure a cultural and national identity that can be exported abroad has overshadowed interest in the true politics of Greek cultural impact, function, and identity.11 We can only hope that the focus on “uniqueness” in contemporary discourse relating to Greek art will not become a paradigm for building the flexible museums and the smart cities of our not-so-collective future.

Green Park panorama [via greenparkathens.wordpress.com]

Despina Zefkili is an art critic and senior editor at Athinorama, the leading cultural guide of Athens, Greece.

References

| ↑1 | Paul B. Preciado, “Qui la dette grecque réchauffe-t-elle?,” Libération, 18/12/2015. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Massimiliano Mollona, artistic director of Athens Biennale Omonoia, “Athens is a workshop of creative ideas and the biennial wants to be their incubator” interview on www.athinorama.gr |

| ↑3 | A first draft of these thoughts was expressed in my lecture “Where will you go after here?” at the Athens School of Art, March 30, 2015, as part of the Soft Power Lectures/Actopolis Athens, curated by Elpida Karaba and Glykeria Stathopoulou and organized by the Goethe Institute. |

| ↑4 | See Despina Zefkili, “Do we need a Greek scene?” Local Folk 3 (2005) and “A place in which map?” Local Folk 5 (2007); Michalis Paparounis, Editorial in GAP 7 (2006); Elpida Karaba and Polina Kosmadaki, “Reading the Greek contemporary art scene: From multi-cultural critique to local meta-theory,” in eds. Elpida Karaba, Kostis Stafilakis, Criticism + Art, Vol. 3 (Athens: AICA Hellas, 2009). |

| ↑5 | The second “Common Ground” meeting of the AICA Hellas on April 1, 2016, was devoted to this “crisis” of criticism. |

| ↑6 | Evangelia Ledaki, “Crisis, narrative representation, artistic explosion,” Avgi Online. |

| ↑7 | The Actopolis lectures are available online at http://blog.goethe.de/actopolis |

| ↑8 | See Elpida Karaba, “The field of curating—10 years after, how to remain a young curator forever,” Avgi Online. |

| ↑9 | Katherine Watson, “The Athens Biennale raises hopes for the institution of the biennial globally,” interview in www.athinorama.gr |

| ↑10 | Kostis Stafilakis has analyzed the connection between the “commons” and the (counter-productive) exoticization of resistance. See Kostis Stafilakis, “Community as an artistic ideology,” in Avgi Online. |

| ↑11 | Angela Dimitrakaki, “(Post)modernism and feminist art history: the reception of the male nude in 20th century Greek painting,” Third Text 64 (September 2003). |