The US-Mexico Border

Share:

A photograph by Pablo López Luz shows an aerial view of the US-Mexico border as it stretches between Tijuana and San Diego County—a mountainous desert bifurcated by a winding ribbon of steel fencing, itself abstracted by distance to little more than a crumpled line against a flattened surface of dark greens and browns. The image lays bare the massive scale of the border and reveals the United States’ efforts to divide and thereby control its often unruly terrain, affecting thousands of human lives.

Tijuana-San Diego County III, Frontera Mexico-USA (2014) is one of five photographs by López Luz included in The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, Possibility at 516 Arts in Albuquerque (January 27–April 14, 2018). The exhibition originally premiered last year at the Craft & Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles as part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. For the show’s Albuquerque iteration, curators Lowery Stokes Sims and Ana Elena Mallet replaced some of the original artworks with works by artists practicing in New Mexico. The result is an exhibition with strong local ties that still retains the curators’ original intentions to survey a broad swath of work by artists grappling with the many ways that the border generates meaning. The exhibition’s subtitle provides a conceptual framework for interpreting the border region: it is at once a geographical location with particular sociopolitical concerns such as migration and commerce, a conceptual place that inspires innovation and longing, and a region rife with potential for utopian futures. The border has been all of these things since its modern-day establishment in the 19th century; the works in The US-Mexico Border reflect the diverse practices thriving today along a nearly 2,000-mile strip of land that defies categorization even as government entities attempt to define it.

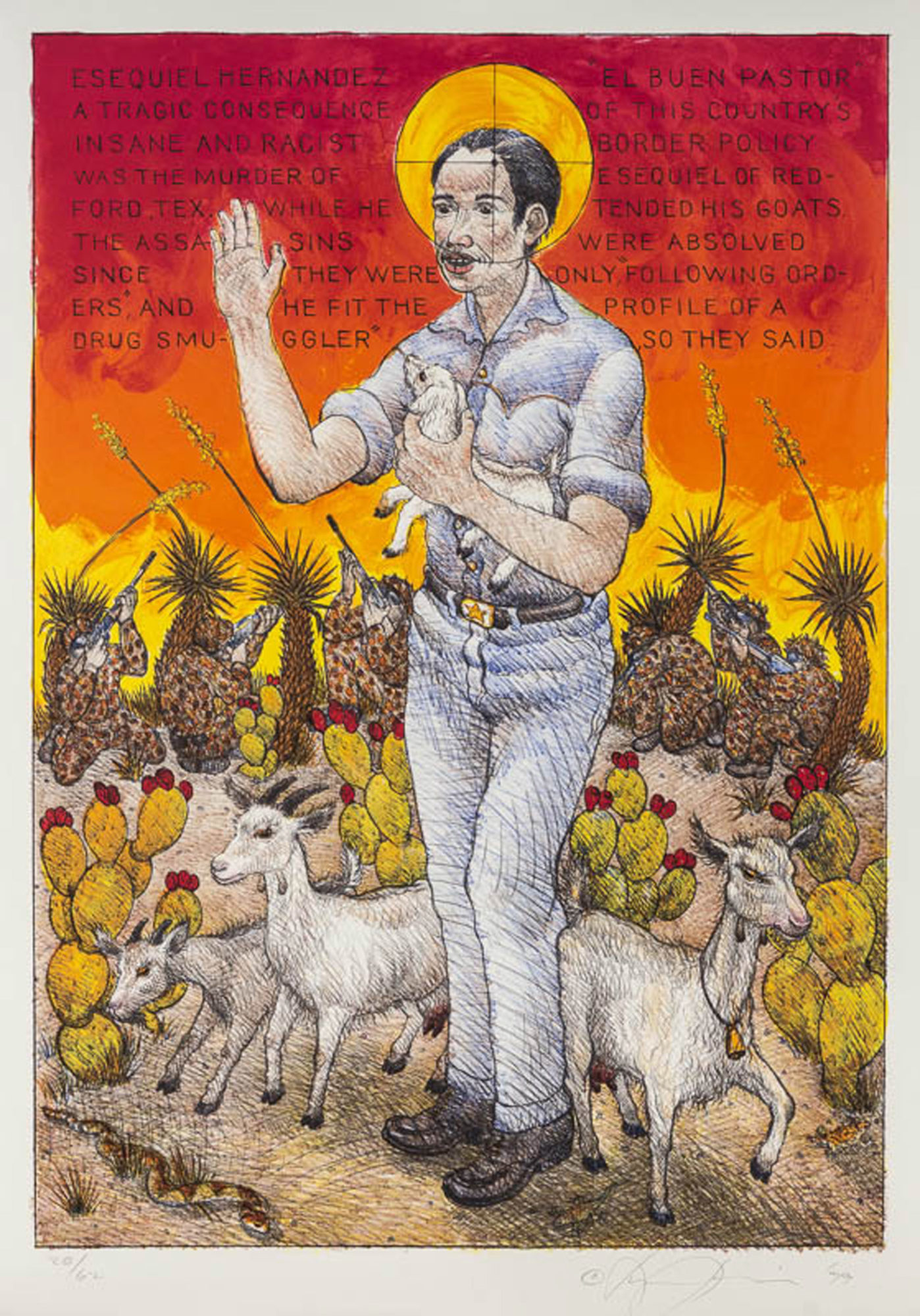

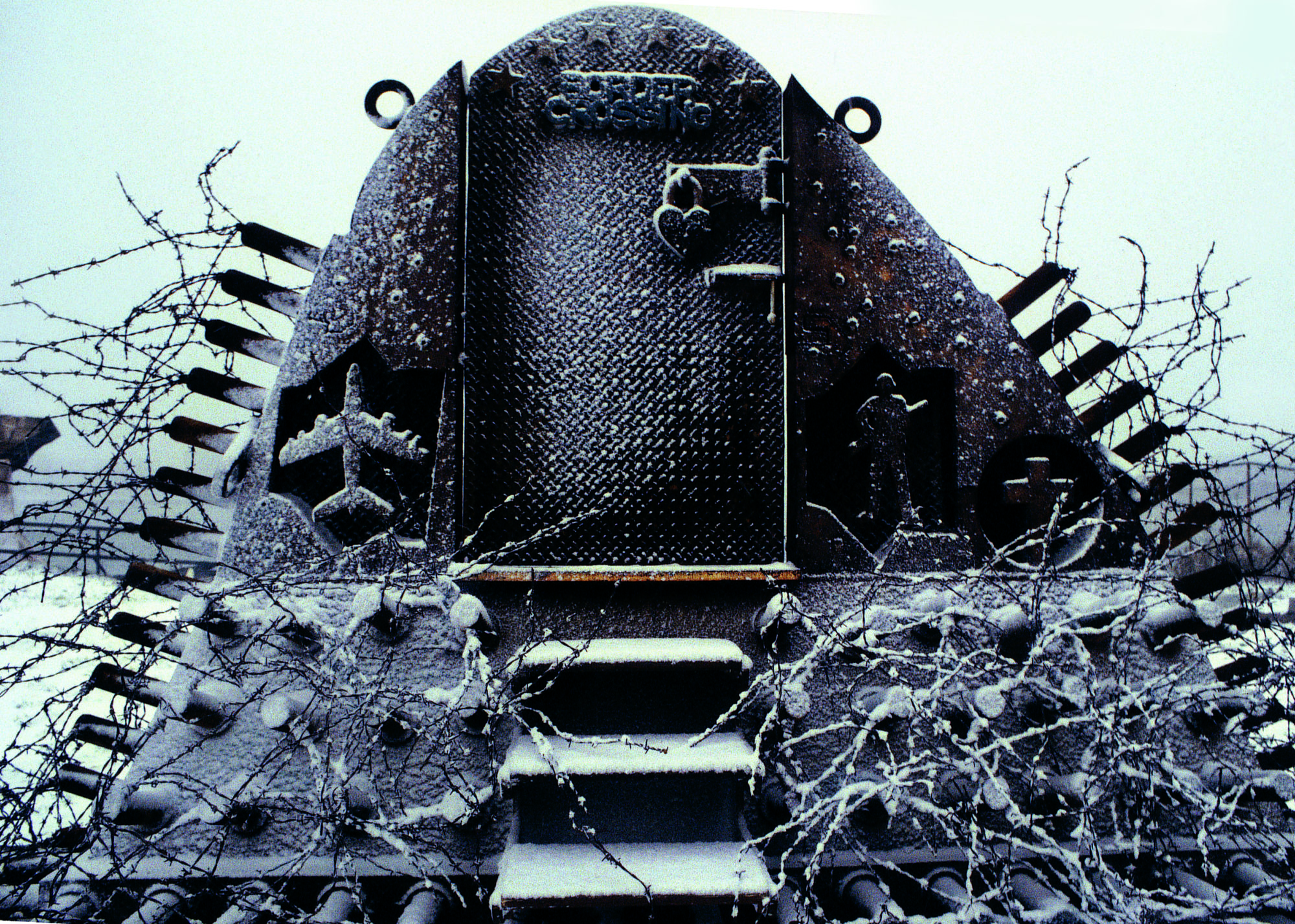

For the many people who cross the border in search of safety or opportunity, migration is a subject with specific material concerns, many of which denote the danger of crossing illegally. Guillermo Galindo’s constructions incorporate abandoned items found along the border, from which he creates new and functional objects. Llantatambores (2015) assembles inner tubes left on the banks of the Rio Grande and scraps of carpet (used by migrants to obscure their footprints) into a set of drums, thus reinforcing the imagination and possibility of the border region while simultaneously echoing the danger inherent in its crossing. Daisy Quezana Ureña’s Untitled (2016), a cast ceramic blouse hung on a steel pole and hovering above a patch of soil obtained near the border, indexes the many bodies that attempt migration. The interior of the shirt glows with a blood-red patina, further intensifying the implications of Quezada Ureña’s delicate sculpture.

A selection of works at the Albuquerque Museum was chosen by curators Andrew Connors and Titus O’Brien to coincide with the 516 Arts show (January 13–April 15, 2018). Among them are themes of migration that resonate in Delilah Montoya’s panoramic photographs of migrant camps in southern Arizona. Detritus such as gas cans and water bottles litter the otherwise tranquil desert landscapes, underscoring the provisional and haphazard nature of migration. Cheap, mass-produced items appear in many representations of the border. Points of entry such as those at Tijuana/San Diego or Juárez/El Paso also foster thriving markets; tourists and residents alike buy imported trinkets, tchotchkes, and souvenirs, as well as handmade goods. Also at the Albuquerque Museum, Adrian Esparza’s Lost in Translation (2018) uses the unraveled threads of a colorful Mexican serape for an intricate wall installation that harks back to the traditions of geometric abstraction that flourished during the mid-20th century in the US and in Latin America. Back at 516 Arts, Esparza’s small-scale drawings of similar compositions mingle with other works that also employ both mass-produced commercial products and handmade craft. They include Jami Porter Lara’s pottery, which employs the traditional Chihuahuan technique of black-firing pottery while echoing the shapes of disposable plastic water bottles. In a similar melding of traditional artisanal practices with images of contemporary commerce, Eduardo Sarabia’s installation A Thin Line Between Love and Hate (2008–2014) features blue-and-white Talavera pottery adorned with images that relate to the thriving and violent Mexican drug trade. Sarabia places his vases atop boxes with misleading labels as if to accommodate smuggling. For some artists, the geography of the border itself was the impetus for creating new goods, such as Andrés Fonseca’s Somos Frontera (We Are All Border People) (2013), a woolen scarf mimicking a map of the border itself, and Alejandra Antón Hornato’s Me Siento como in México (2015), a wicker chair inspired by the shape of Mexico.

Altogether, nearly 50 artists contributed to the exhibitions at 516 Arts and the Albuquerque Museum. Their artworks make clear that the US-Mexico border is anything but the clean line represented in Luz’s aerial photograph. Since its inception, the border has been contested and shifting, its inhabitants constantly interacting with one another across both sides. These exhibitions, like the border itself, are capacious; to expand the dialogue, a series of talks, film screenings, and workshops on the art, design, and politics of the border are to take place in various venues across Albuquerque through April.